by Pedro Cabello del Moral

I am sure that anybody reading this post has at some point used (or considered using) media in the classroom. Whether for making lectures more appealing, for illustrating a particular concept, or for a creative in-classroom activity, media offers a powerful teaching aid.

Does that mean that all media our students consume is harmless? Absolutely not! Films, photos, music videos, audios, social media snippets, etc. can damage our students’ sense of safety. They can trigger fear, shame, and many other negative emotions. These media may be complicit with the systems of oppression that we critique in our classes. They may manipulate the facts and contribute to systems of surveillance. Many would argue that young people today are overly-exposed to all kinds of media in their daily lives. Do we really need to show them more in our classrooms? Having conversations about media is key to helping our students build skills in critical thinking. The recently developed theoretical framework known as Critical Media Literacy (CML)1 can help us affirm the positive effects of media in learning environments while also deconstructing false impressions of objectivity.

Unpacking Critical Media Literacies

To unpack CML, we can start by asking why media matters, why literacy matters, and why it is necessary to adopt a critical perspective.

Media broadly refers to analog or digital video, audio, and still images available for playback or streaming. CML focuses less on the object itself than on the circulation of media and the mediatic universe that connects products, authors, and users/spectators. Put another way, CML addresses the contexts in which different media are shared, curated, produced, and self-produced, and the way they document/represent/define people. For instance, we might screen a music video or a commercial in a class that we are teaching and begin asking questions about the intent, the production process, or the recipients of that video. Later, we could try to find similar works that influence or are influenced by its aesthetics and narrative form.

Literacy implies the capacity of students and instructors to understand, analyze, create, and research media. Media literacy takes into account the continuity and interconnection between these processes. For instance, when students have had the experience of creating their own film-essays, they are in a better position to understand the production process of film and TV and the politics behind those processes. There are many paths toward media literacy depending on the level of mastery of each interconnected process. That is why it seems important to talk about literacies in plural. Douglas Kellner and Jeff Share in The Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education pose that “literacies must be constantly evolving to embrace new technologies and forms of culture and communication, and must be critical, teaching students to become discerning readers, interpreters, and producers of media texts and new types of social communication.” (2019, 13).

The framework of Critical Media Literacies serves students in several aspects. At a first level, CML deconstructs myths and denaturalizes media representations, encouraging students to identify sexist, racist, classist, or homophobic messages and to question “how these oppressive ideologies are sustained and normalized” (Kellner and Share 2019, 12). Once students develop such critical skills, they are better equipped to create alternative readings, and eventually, to develop counterhegemonic media. Keller and Share tie the CML project to radical participatory democracy (1994, 372). Alison Butler in Educating Media Literacy: The Need for Critical Media Literacy in Teacher Education encourages us to welcome this transformative potential: “When young people are granted the opportunity to critique their surroundings, they may very well critique their teachers, classrooms, and communities.” (2019, 8).

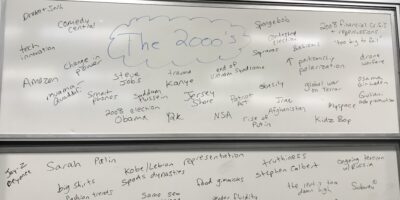

It seems obvious that CML in the classroom is a collective and multidirectional project. It links with the idea of “participatory culture” developed by Henry Jenkins (2006). A participatory culture entails support for creating and sharing with others and for making every contribution matter. This is possible thanks to informally acquired literacies and technical savvy through social media. The CML framework invites instructors to welcome these complex and heterogeneous literacies in order to create student-centered media corpuses for the courses they are teaching. In the same vein, CML is not about originality and proprietorial rights. It embraces the remix culture that our students are part of. Images, audios, and videos are constantly copied, remediated, and re-edited. Approaching media through a remix philosophy might result in a more engaging experience for our students.

Key concepts

One of the most important aspects of the CML approach is related to representations. As Butler summarizes, representation is the result of events made into “stories which invite audiences to see the world in one way and not in others.” (2019, 10). As a consequence, media normalizes certain identities, behaviors, or abilities and constructs stereotypes.

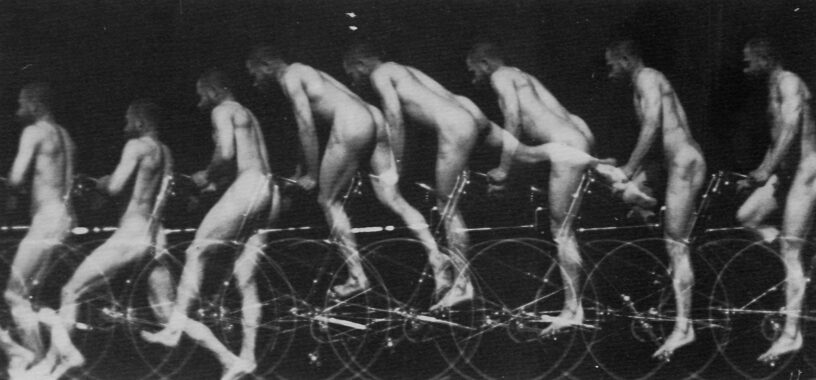

The gaze is one of the processes by which these stereotypes are reinforced and reproduced. It assumes a visual relationship of domination that triangulates the author(s)/producer(s), the spectator, and the characters depicted. Laura Mulvey’s groundbreaking essay “Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure” released in 1975 analyzed the process by which commercial cinema is made by and for the male gaze. Hollywood cinema, in particular, represents time and again the male character/protagonist as the bearer of the look, and the female character as the object. Those repeated visual scripts do not lead to faithful and multifaceted representation of women in the characters on screen. Mulvey’s take on the male gaze is succinctly explained in this video.

The male gaze is just one of the components of a way of looking that, apart from masculine, is mainly Eurocentric, heterosexual and ableist. The gaze is rarely univocal, and it is normally the product of interconnected structures of oppression manifested through visual regimes. In relation to the gaze and representation, other concepts that can help deconstruct complex media imaginaries in our discussions with students include commodification, orientalism, colonial gaze, fetishization, female gaze, and ableist gaze.

Challenging representations entails a joint critique of the politics of race, gender, sexual identity and ability in media. bell hooks’ oppositional approach to media-viewing sheds light on central aspects of representations and spectatorship. She critiques the unwillingness to engage critically with movies’ stereotypes and denigrating portrayals, especially of women of color, by filmmakers, critics, and viewers who invoke the mantra of documenting life “as is”. Accountability matters. We should hold media and their creators accountable. For hooks, accountability “never diminishes artistic integrity or an artistic vision, it strengthens and enhances” (1996, 9). But it works differently depending on who is behind the production. hooks complains that white male filmmakers do not have to deal with race, they can make movies with all white characters and “their ‘right’ to do so is not questioned” (1996, 69). On the other hand, when any filmmaker of color focuses on people of color, they are normally asked to justify their choices and “assume political accountability for the quality of their representations” (1996, 69). Filmmakers of color are equally scrutinized when they decide to feature only white characters. The double standard in aesthetic accountability and the burden of representations are questions that we can confront any media text with (not only the ones that openly talk about race, or for the same matter, gender, sexuality or ability) in class discussions with our students. As hooks says: “Whether we like it or not, cinema assumes a pedagogical role in the lives of many people. It may not be the intent of the filmmaker to teach audiences anything, but that does not mean that lessons are not learned” (1996, 2).

There are useful tools that we can use with our students to direct their attention to the disproportionate predominance of white, male, heterosexual, young, and able-bodied protagonists. The Bechdel test for movies, created by cartoonist Alison Bechdel, helps us understand the extent to which a given movie attempts to represent women as complex characters. It based on three simple questions: Does the movie feature more than one female character? Do these female characters engage in a conversation? Does the conversation revolve around something other than men? As this video and these data visualizations show, the number of movies that do not pass the test is astonishing. Whether the scope of the Bechdel test is too narrow is a question open to discussion. As a matter of fact, the Bechdel test sparked the creation of other tests to detect stereotypes in movies.

Oftentimes, the best way to engage in meaningful critiques of the abovementioned concepts is to challenge them in practice. The CML framework encourages media-making in the classroom to reflect on the politics of production, circulation, and viewership. For our students, making video essays, documentaries, and podcasts can be a great opportunity to express their identities and voice collective demands. Critical Media Literacies is not necessarily about achieving formal quality and a professional look. Instead, educators are encouraged to focus on democratizing the means of production and building collective informal expertise. We don’t need to give students formal training in film or media production in order for them to produce insightful and counterhegemonic images and narratives in their projects.

The many components of Critical Media Literacies and the multifarious ways we can implement this framework in our courses might feel a bit overwhelming, especially for those readers who are new to the topic. We can rather see CML as a horizon and not necessarily a full-fledged goal. CML can be built progressively through small interventions. For instance, we might juxtapose the media used in our lectures with other works that represent different voices. We might opt for longer class discussions after screening videos to provide time for critical analysis. We might introduce media-making assignments into our syllabi as an alternative to the standard final paper. These are just a few ideas, but every instructor can find their own way to CML in conjunction with the rest of the class participants. The fact that CML may look very different from one course to another is both challenging and rewarding.

Further resources

- CML research guides: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/educ466

- Critical Media Literacy and Civic Learning: https://edtechbooks.org/mediaandciviclearning

- National Council of Teachers of English Report on CML: https://www.canva.com/design/DAERz0BpJyk/I4sPUxfrZlHLVys3QIVilQ/view?utm_content=DAERz0BpJyk&utm_campaign=designshare&utm_medium=link&utm_source=homepage_design_menu#1

- Critical Media Project: https://criticalmediaproject.org/

Notes

1. The concept first appears in Carmen Luke’s 1994 article Feminist Pedagogy and Critical Media Literacy as a framework for undergraduate liberal arts curriculum. CML builds upon ideas from feminist pedagogy, cultural studies, and critiques of postmodernism. In 2005, Douglas Kellner and Jeff Share relaunched the concept with a programmatic intention, as they lay out an extensive conceptualization and methodology.

References

Butler, Alison. Educating Media Literacy: The Need for Critical Media Literacy in Teacher Education. Brill, 2019

hooks, bell. Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies. Routledge, 1996.

Jenkins, Henry et al. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. McArthur Foundation, 2006.

Kellner, Douglas and Jeff Share. “Toward Critical Media Literacy: Core Concepts, Debates, Organizations, and Policy.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education Vol.26, No.3 (2005): 369-386.

Kellner, Douglas and Jeff Share. The Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education. Brill, 2019.

Luke, Carmen. “Feminist Pedagogy and Critical Media Literacy.” Journal of Communication Inquiry, No. 18 vol. 2 (1994): 30-47.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, 1975.

Notes

- The concept first appears in Carmen Luke’s 1994 article Feminist Pedagogy and Critical Media Literacy as a framework for undergraduate liberal arts curriculum. CML builds upon ideas from feminist pedagogy, cultural studies, and critiques of postmodernism. In 2005, Douglas Kellner and Jeff Share relaunched the concept with a programmatic intention, as they lay out an extensive conceptualization and methodology.

Leave a Reply