By Katie Uva

Over the past year at the TLC, we’ve been diving deeper into the question of care in the college classroom. In a post for Visible Pedagogy last September, Luke Waltzer laid out ideas that would guide the TLC’s work going forward: abolitionist pedagogy, care and social and emotional wellness, connection and sense making, student-centered and active learning, and ethical educational technology, ideas that are also reflected in last year’s substantial revision of our Handbook Principles. These priorities have taken shape against a wider educational context–in schools at all levels and all throughout the country, students and instructors are trying to learn and to teach and to build relationships while being rocked by disruptions to their education, by struggles with educational technology, by uncertainty about their safety and stability due to COVID-19, and by the presence of racist violence and other systemic challenges that affect life in school and outside of it.

This is a time of tremendous tension and unpredictability, and one of the chief sources of conflict that has been reignited among educators is the concept of rigor. A recent flurry of articles (and the Twitter discourse that accompanied them) throws into stark relief some of the fault lines in the rigor conversation. Deborah J. Cohan, writing for Inside Higher Ed, expresses frustration with teachers’ aversion to giving low or failing grades during the pandemic, describing that inclination as “compensatory charades” and “people-pleasing cartwheels.” To her, more flexibility toward students is an attack on rigorous teaching, one that runs the risk of enabling “lazy” or evasive behavior and undermines the integrity of individual instructors and the institution as a whole. On the other hand, Jordynn Jack and Viji Sathy in The Chronicle of Higher Education argued recently that “it’s time we recognize ‘rigor’ for the exclusionary concept that it is and for the preferential practices it usually promotes,” and do away with it–they perhaps archly use the word “cancel”–in favor of other goals and priorities.

Last April, TLC Fellow Atasi Das and I facilitated a conversation with the rest of the TLC staff about these issues of rigor. First, we worked to define the term and see whether we were all in fact referring to the same thing when we talk about rigor. Second, we talked as a group about what our personal experiences of rigor have been–as students and as instructors. Lastly, we wanted to explore whether we thought rigor is reformable and should be a priority, or whether something else might replace it as a guiding principle.

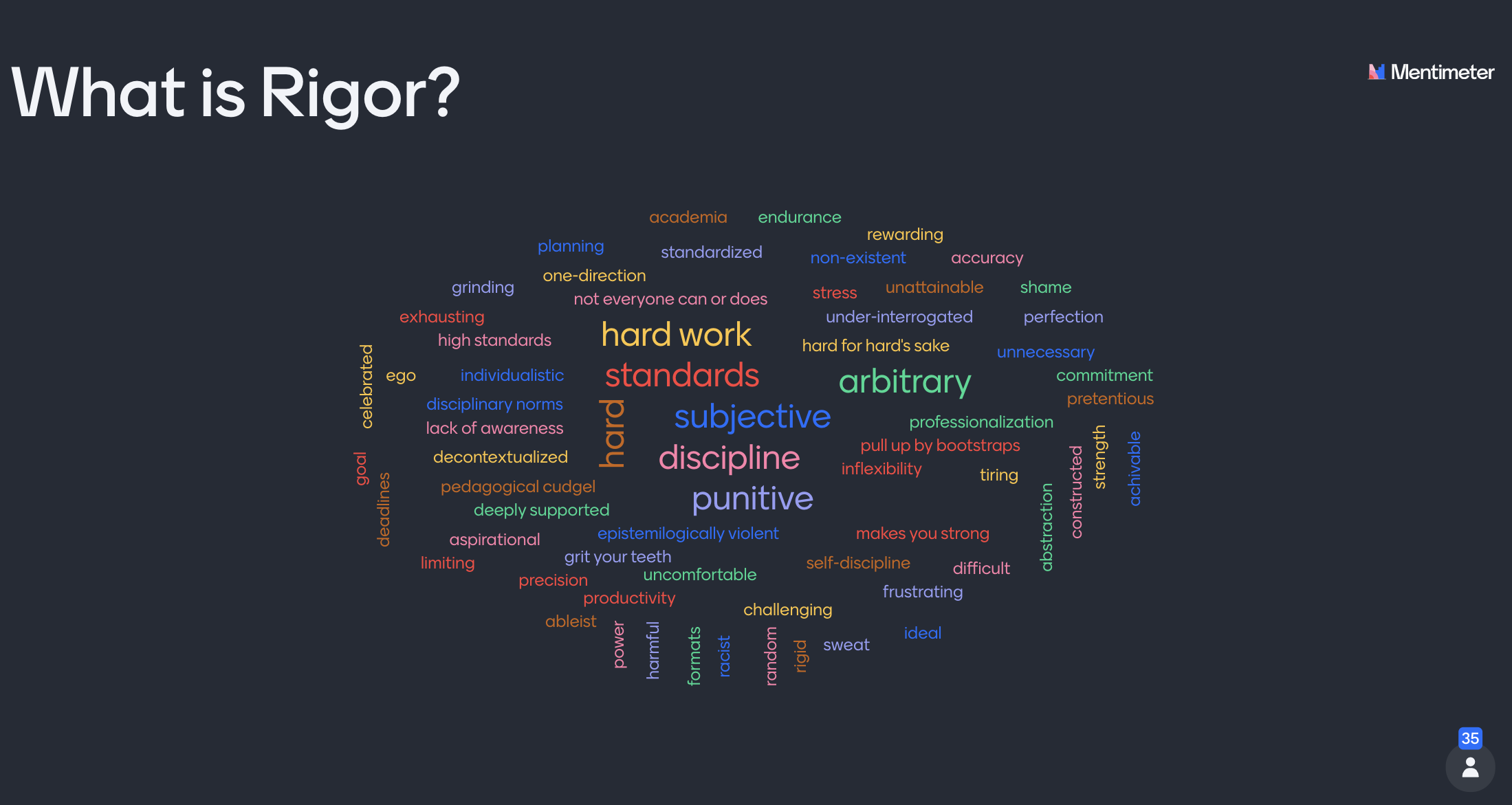

We started with a word cloud exercise, asking everyone to take two minutes and list what comes to mind when they hear the word “rigor.” The results demonstrated the complex and often contradictory nature of this idea–some answers, like “rewarding,” “aspirational,” or “achievable” implied potential benefits of rigor, while many like “subjective,” “arbitrary,” “racist,” and “shame” highlighted rigor’s ambiguity and potential for harm.

Rigor Word Cloud. This image was generated by TLC staff using Menti.com and is licensed under a CC-BY-NC license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

In talking through our own experiences with rigor, we noticed that rigor functions on many scales at once–on an institutional level, within a discipline, within a classroom, and also within an individual’s sense of self. As graduate students who are also teaching, many of us have experienced colleagues trying to relate to us by complaining about students’ perceived “laziness,” or expressing frustration and incredulity that students don’t know something or are unfamiliar with certain classroom norms–a “they should know this” mentality, often bolstered by the claim that “it’s not my job to teach them [x skill].”

This connects to a perception among many TLC staff that the idea of rigor is used to weed out students and determine worthiness in the eyes of the institution, a practice that typically privileges students who are most oriented toward pleasing the instructor and most skillful in navigating the hidden curriculum. One breakout group also noted the toll this takes on teachers–because there is little space in higher education for vulnerability and because college instructors are pulled in so many different directions by their various responsibilities, there’s a frequent slide from a feeling of being overwhelmed or a fear that you’re not teaching effectively to placing blame on the students or lashing out at the students when they don’t meet expectations. Several of us noted the persistence of potential emotional abuse as a mark of rigor–in multiple disciplines, we’ve experienced rigor framed as “strength,” schooling as a process of “toughening you up for the real world,” and crying students–at the K-12, undergraduate, and doctoral levels–as a sign of a rigorous teacher.

But is there nothing redeemable at all about rigor? One breakout group saw rigor as fundamental to the educational process–that rigorous standards, when expressed clearly and supportively with room for input from the student, could provide students a gentle and steady push forward, could prompt them to think more deeply and more analytically and practice discipline-specific skills, and in the end could supply them with the liberating experience of having been challenged in a way that was meaningful to them and useful in pursuing their own ambitions.

There were clear differences of opinion within the group about whether rigor is useful as a standard or not. For some of us at the TLC, rigor is a concept that is so illegible and has such a track record of harm and of being weaponized against inclusion that we’d prefer to promote a different standard as the guiding star of our teaching–participants mentioned “care,” “collaboration,” “inquiry,” and “growth” as potential candidates.

For those of us in the TLC who do see something redeemable in rigor, though, it is clear that in order to be useful rigor needs significant clarification and revision. Any continued pursuit of rigor as a guideline for our teaching depends on deep reflection about why we think it’s important, what exactly we’re referring to when we say rigor, and an obligation to ask for rigor from ourselves as well–rigorous introspection, rigorous flexibility, rigorous receptivity to student feedback. Whether we’re continuing to embrace the idea of rigor or rejecting it in favor of other values, some persistent ideas that emerged from our group conversation to support students while mitigating harm include:

- Not pitting students against each other. Classes where only a certain percentage of the class can receive a top grade makes students into adversaries. Refusing to respond or adapt to an individual student’s needs because “everyone else in the class did it” unwittingly enlists the rest of the class in punishing a single student.

- Working collaboratively. Setting norms and standards as a group gives students more power in the class, shows respect for their judgment, and also engages them more fully in determining what a fair standard is and why. In addition, having students work on assignments together encourages them to feel more invested in the class because they are responsible to each other and also provides more room for students to learn from each other and work through challenges collectively.

- Teach the skills your class requires. Scaffolded assignments and the building of skills that fuel the assignment ensures you’re all on the same page and produces less frustration on everyone’s part when the final assignment is due. Professors often vary in what they want, and it’s worth it to clarify your standards and model the skills for the class. This can take the form of a class session led by the instructor, a visit to the library for a workshop with a librarian, prerecorded short video tutorials that students can access asynchronously, or at least providing vetted resources that students can refer to as needed or check first before setting up a meeting with you to discuss obstacles.

This has been a challenging period indeed for higher education, but in taking the time to assess our values as educators we afford ourselves an opportunity to build stronger relationships with our students and promote deeper understanding of the subjects we teach. To borrow a concept from museum studies, the college classroom is not only “about something,” it’s also “for somebody.” A substantive reassessment of rigor helps us balance our responsibility to teach the content of our specific subjects and the standards of our particular disciplines with our responsibility to support the intellectual journey and emotional wellbeing of each of our students.

We had a fruitful discussion within the TLC about rigor this past spring, and many elements of that conversation are still unfolding in our work and thinking. We invite you to explore the timely and complex question of rigor with us. What does rigor mean to you? Where have you encountered it or been expected to uphold it? What needs to exist in an educational setting for rigor to be employed in a way that is conscientious and beneficial to the student? What principle or principles guide your teaching?

Katie Uva is a PhD candidate in History at the CUNY Graduate Center and the Manager of Editorial Projects at the TLC.

References

Cohan, Deborah J. “Upholding Rigor at Pandemic U.” Inside Higher Ed. August 25, 2021. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/08/25/professors-should-uphold-rigor-when-assessing-students-even-pandemic-opinion

Jack, Jordynn and Viji Sathy. “It’s Time to Cancel the Word ‘Rigor.’” The Chronicle of Higher Education. September 24, 2021. https://www-chronicle-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/article/its-time-to-cancel-the-word-rigor

“Chapter 2: Foundational Principles.” The Teach@CUNY Handbook Version 4.0. 2021. https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/teach-cuny-handbook-v-4-0-9f476bea-837e-42ac-a555-d114f8426d50/section/8863ff28-abbb-4747-8e1e-fd902bea1ca0

“Hidden Curriculum Definition.” The Glossary of Education Reform. July 13, 2015. https://www.edglossary.org/hidden-curriculum/

Walia, Dhipinder. “Driving Through the ‘Inclusion Jeopardizes Rigor’ Rationale: A Travel Guide to Keep From Stalling.” Visible Pedagogy, January 15, 2020. https://vp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2020/01/15/driving-through-the-inclusion-jeapordizes-rigor-rationale-a-travel-guide-to-keep-from-stalling/

Waltzer, Luke. “Teaching in These Times: The TLC’s Guiding Principles for the Academic Year.” Visible Pedagogy, September 23, 2020. https://vp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2020/09/23/teaching-in-these-times-the-tlcs-guiding-principles-for-the-academic-year/

Weil, Stephen E. “From Being about Something to Being for Somebody: The Ongoing Transformation of the American Museum,” Daedalus Vol. 128, No. 3, America’s Museums (Summer, 1999), pp. 229-258.

Daniel Lisa

Walia, Dhipinder. “Driving Through the ‘Inclusion Jeopardizes Rigor’ Rationale: A Travel Guide to Keep From Stalling.” Visible Pedagogy, January 15, 2020. https://carparkingzoid.com/