By Sarah Litvin

Of the activities I helped design for staff trainings at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, where I worked from 2008 until 2013, my favorite was the “Object Biography.” The idea was to send our staff into the recreated historic spaces of the tenements’ apartments—spaces they led visitors through every day—and write the biography of one artifact. Which family member first bought or acquired it? Where and how? Who used it or interacted with it on a daily basis? Were they proud of it? Were they embarrassed by it? Would this object stay with the family when they moved, or would it be sold or discarded?

While the biographies my colleagues wrote were, unquestionably, non-factual, the process of writing them was extremely valuable. In asking our staff to consider these questions, we were asking them to call on their knowledge of this particular object, the social mores of the time, the family members’ personalities, and even more, to synthesize this information, and to use it to make hypotheses about the significance of this object to the family.

The museum has since found a brilliant, public-facing application of the “Object Biographies” exercise: an online, crowd-sourced exhibit called “Your Story, Our Story.” It’s designed to “turn students into historians” and I found it to be both a productive and popular short writing assignment in my immigration history class at John Jay College. (Professors can even create a “tag” to keep their class’s entries together) Check out the project guide for college instructors created by the museum, and the assignment I created for my class.

The idea that an object can be a powerful nexus for storytelling and meaning-making is central to museum educators’ theories and practices of teaching and learning. But it’s an underutilized method of instruction in the college classroom. In this post, I’ll share how my colleague Samantha Gomez-Ferrer and I designed an object-based exhibit to construct an historical narrative about the Reher Center. Hopefully, you will find our experience helpful in writing your own object-based classroom assignments or teaching narratives.

Writing a Story and Choosing Objects

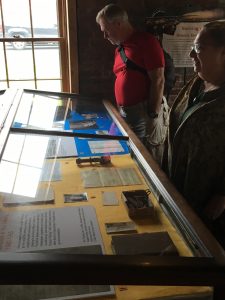

In Mid-August, my colleague Samantha and I were invited to install an artifact exhibit on behalf of the Reher Center in a case at the Matthewis Persen House Museum, an amazing 18th-century historic site in the Uptown neighborhood of Kingston, NY. To get started, we asked ourselves two main questions: What story did we want to tell, and which objects from our collection would most effectively tell it?

Running through my mind were the wise words of Valerie Paley, Chief Historian of the New-York Historical Society: “History exhibits begin with a story, not a checklist of objects.” We wanted to offer a compelling narrative that would give folks a preview of our site and pique their interest to learn more. We also had to think about the logistics of the space (in this case, a long, rectangular display case segmented into quadrants) and consider the background knowledge and interest of our audience, much as teachers do in adapting a course for a new semester.

“Rising Time” Exhibit

In the end, we decided to tell a story that featured photos, documents, and objects from our building to tell twin stories of continuity and change in the Rondout neighborhood between 1870 and 2004. We called the exhibit “Rising Time,” and each quadrant in the case contained a chronological “scene” that started with a large image and an introductory “section panel” of text that connected the story of the building with what was happening in the neighborhood. Within each “scene,” we included a selection of artifacts from the building’s former tenants to “people” the story and offer visitors snippets of life at 99-101 Broadway during each era.

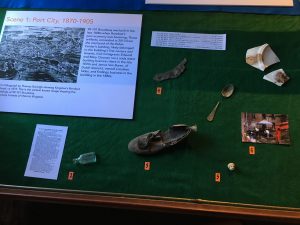

“Rising Time” Scene 1

Samantha and I used our best judgement to select objects that would not only help narrate our story, but which were visually compelling, represented different parts of the collection and (significantly!) fit into the case. You can explore many of the artifacts we chose by visiting the Reher Center’s Digital Collection.

Storytelling Through Objects

For me, the most important selection criterion was whether I could use each object in our exhibit to tell—not just illustrate—our story. Because I wanted more space to narrate than the typical identifying labels would allow, I decided to write an Exhibit Guide to offer interpretations or provocations I hoped would encourage visitors to look closely and consider how each item related to the exhibit’s larger themes.

For example, consider this description of a porcelain doll’s head, plate, and spoon, visible in the photo of Scene 1 (above), which were excavated from an archeological dig at the Reher Center in 2012:

Porcelain Doll’s Head, Plate and Spoon, about 1890-1910. In the early 1900s, several working-class immigrant families rented the apartments at 101 Broadway. We might imagine that 9-year-old Anna Jordan, whose parents were Irish, was crushed when her porcelain doll’s head broke off, or that Anna Sills, a homemaker living here in 1905, cooked with this plate and spoon for her German-born husband and five American-born children.

By linking together information I gleaned from the census record with artifacts excavated from the yard, I encouraged visitors to join me in seeing more than just the materiality of these objects. Drawing from the methodology of the object biographies, I tried to encourage visitors to imagine these items as things that were used by people not so unlike themselves. This, in turn, helped me to paint the larger picture of the Rondout as a German and Irish immigrant neighborhood in the late-nineteenth century.

Your Turn

As an experiment, choose one lesson that you plan to teach this semester, and write it out as a story. Who are the main characters, what are the plot points, and what props might you bring in to help you bring that story to life?

Sarah Litvin is a doctoral candidate in History and a writing fellow at the TLC.

Leave a Reply