By Dhipinder Walia

I prepare for a new semester the same way I imagine so many of us do: with a syllabus of hopes and commitments, a notebook of cool ideas shared by colleagues on campus, posts from Visible Pedagogy, etc., and a final project that “will get it right this time.” This semester, I was excited to work with students on developing a community-facing project. A colleague at Lehman College taught a Social Issues and Writing course where students conducted research on a particular local issue and then proposed an intervention in the form of a presentation or a paper. I was inspired and sure that a scaffolded version of that project could meet the objectives of English Composition while also getting at the heart of my own pedagogical commitment to inclusive, student-centered learning. The goal was to ask students to take their 5 to 7 page autoethnography (1) and transform it into an artifact meant for a particular community. Thomas Dean’s Writing Partnerships: Service-Learning in Composition, published in 2000, describes his reasons for using community writing, “In my courses, I want to encourage versatile and reflective writers who not only learn strategies for negotiating the writing challenges of college but also venture beyond the classroom (and beyond academic discourse) to serve their communities by applying their…literacy skills to pressing social problems” (52).

I planned my syllabus so students would be finished with final drafts of their autoethnography in April, and we could spend the last month of the semester working in groups, brainstorming local agencies that might benefit and/or add on to students’ research, and preparing community-facing artifacts that could range from playlists (2) to zines. That was the plan.

But then COVID19 happened.

Some students dropped the course immediately in March. Other students needed to disappear for a bit, attending to their families, new life circumstances, mental health, all of the above. And even more students were sharing that work schedule changes at hospitals and grocery stores made it nearly impossible to complete assignments. Not to mention most campus facilities were/are shut down, so many students who relied on the library to get work done had to make do with less than ideal alternatives.

There’s no way to transcribe how we all got from March to now, the end of the semester. So I won’t try to offer a neat transition. Instead, I’ll share two strategies that helped me facilitate learning during a pandemic.

First, I immediately let my students know that our goal for the rest of the semester would be to “do what we can.” I wrote to each of them individually and asked that they let me know what assignments they’d be able to complete by the end of the semester. Some students emailed right away with, “I am fine. I can do it all.” Other students waited a few weeks and wrote, “I don’t know.” I let each student know individually that I was instituting an “A for effort” grading policy (3).

Second, I made individual assignments collaborative. Rather than have students take their individual autoethnographies and transform it into something community-facing, I asked students if they’d be okay with working on a project as a class (using a google poll). 22/22 students responded yes to a class project (which I think suggests just how much we missed being in a classroom together). In order to facilitate a relatively stress-free class project, I made all of the collaboration asynchronous. I opted for asynchronous group work because in my own classes at the Graduate Center, I found live-zoom sessions invasive. Of course, I have come to appreciate my professors’ dedication to maintaining some type of normalcy, but it wasn’t an easy process. Some days, I’d end sessions with a migraine and in tears because sound would cut off, or I just didn’t want to see my face for two hours. Looking back, I know I projected my own negative feelings of synchronous zoom meetings onto my students, but the asynchronous model worked! It worked well.

Every few days I would share a google doc with a task. I asked students to participate on the google doc if and when they could. Again, we were really holding to the “Do what we can” model. First, students shared possible ideas for a community-facing project. Then, students voted on which idea they wanted to move forward with. Next, students narrowed down the focus of the idea voted on. Ultimately, they decided on a zine for New Yorkers about how to preserve mental and physical health while under quarantine (4). The final google doc I created was a “sign-up” sheet. I asked for everyone to sign up to complete a task toward this zine. I made it clear that the task should be whatever they were up for. Some signed up individually or in pairs to create pages, others shared they’d proofread a page, and a few volunteered to share testimony of their experiences on the front lines.

The final product is a 32-page zine titled, “We Stand Together.”

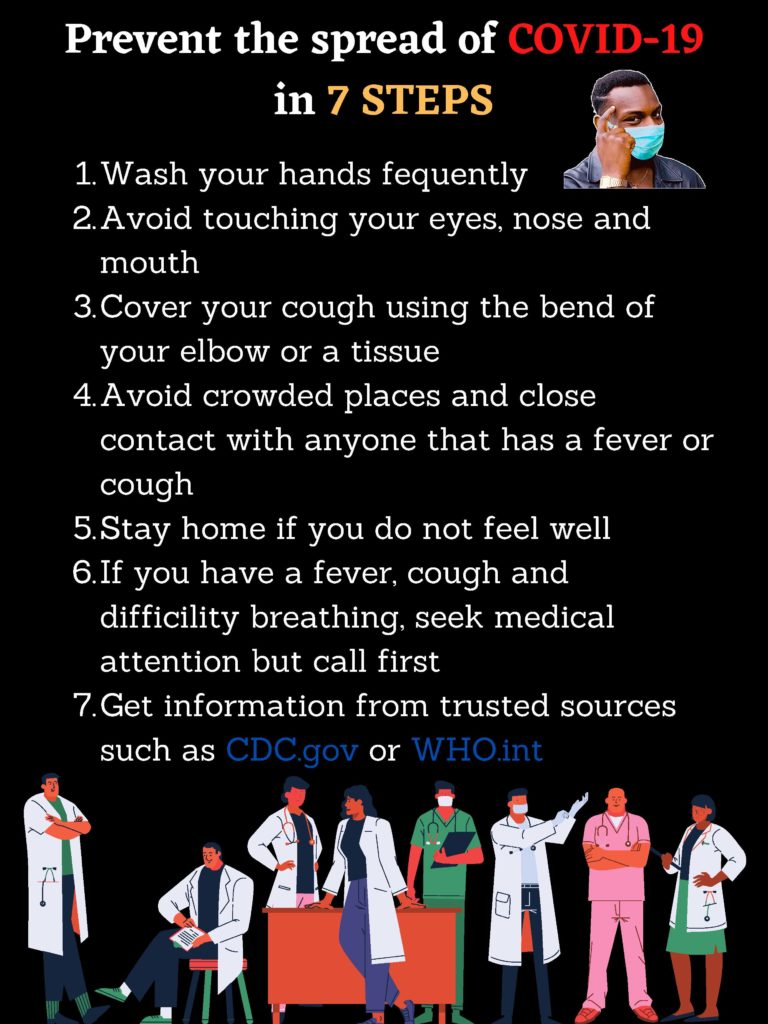

Page from zine on staying healthy during COVID19

I started this post with a reflection on how I wanted to incorporate community-facing writing into the classroom as a way to get students thinking about literacy practices beyond the college classroom. Yet during a pandemic, when all of us were literally thrown out of the classroom, community writing became something more. This zine became our method of building a community outside of the classroom. It became our only way of recording the material ways we learned from one another. It is my only way of sharing how I taught (with students’ support) during a pandemic: We did what we could.

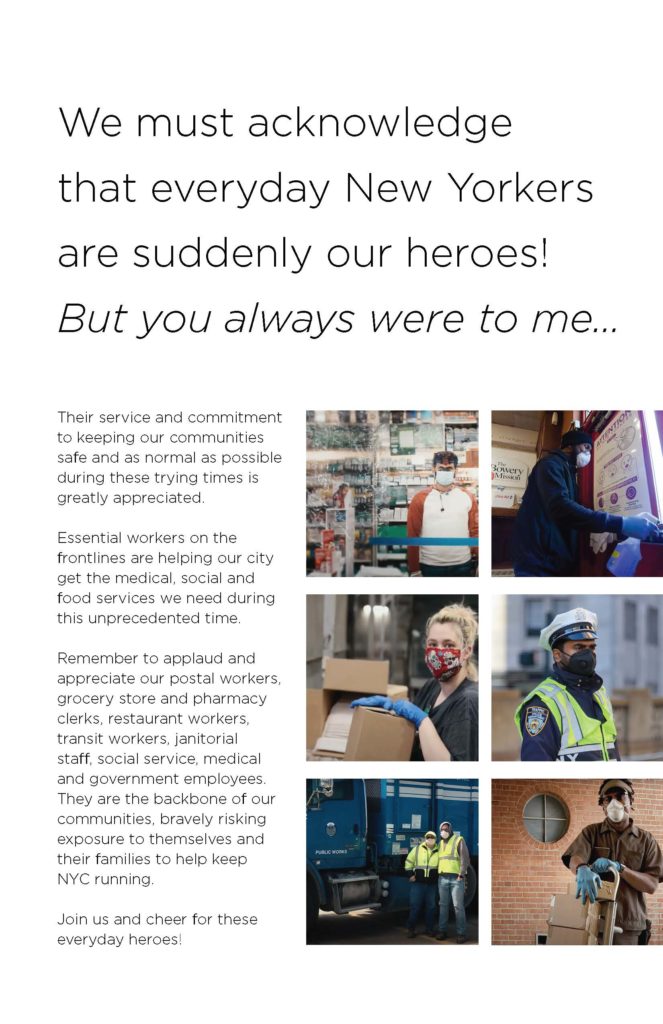

Page from zine on acknowledging New Yorkers

[1] For more information on autoethnographies, see Teaching Autoethnography, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-teaching-autoethnography/chapter/introduction/

[2] Last semester, a student wrote a project on their relationship to food. I thought of this student and her love for sharing dope playlists with all of us. I imagined if she were in this iteration of my course, she might’ve opted to develop a playlist of body-positive songs for teenagers dealing with their own set of body image issues.

[3] For more on why A for All is the ideal grading strategy during a pandemic, check out a collaborative piece I co-authored, https://medium.com/@conortomasreed/a-for-all-yes-all-transforming-grading-during-covid-19-a3a24de4e249

[4] To say I was thrilled by their idea for a zine about preserving mental and physical health would be an understatement.

Dhipinder Walia is an English PhD candidate at the Graduate Center as well as a full-time lecturer at Lehman College.

Leave a Reply