by Dhipinder Walia

On paper, I love collaborative learning and writing. I understand peer-editing creates possibilities for student-centered revision practices. Similarly, I have experienced the space group projects create in the classroom for diverse learning styles. The link between collaborative learning and inclusivity (1) is an obvious one, so why the resistance?

Bruffee defines collaborative learning as, “establish(ing) and maintain(ing) knowledge among a community of knowledgeable peers…”(2) Caspi and Blau conclude collaborative learning (referring to peer-editing specifically) is a process of losing singular ownership, yet maintaining perceived learning outcomes, and improving quality of writing (3). Davidson celebrates collaborative learning as a student-centered pedagogical model (4) that prevents what Friere explained as the banking concept of education (5).

With such noted pedagogues proving the value of collaboration, I didn’t understand why every semester, I was still resistant to group projects, peer-editing workshops, and student-designed syllabi. After reflection, I’ve come up with a possible reason: When you make room in the classroom for collaborative learning/writing, you also make room for messiness and failure. I’m terrified of both in the classroom.

Yet, this semester, with the support of CUNY’s Focused Interest Group (FIG), I decided to design an assignment for English Composition Writing II that foregrounded messiness and failure: the zine (6). The project would be to work in groups of twos and fours to develop and publish a zine related to the first half of the semester’s theme: higher education.

What follows are three strategies used in presenting and facilitating the zine assignment that I believe centered collaborative pedagogy, but also assuaged my fear of failing (and becoming a hot mess):

- Where’s your zine, Professor?

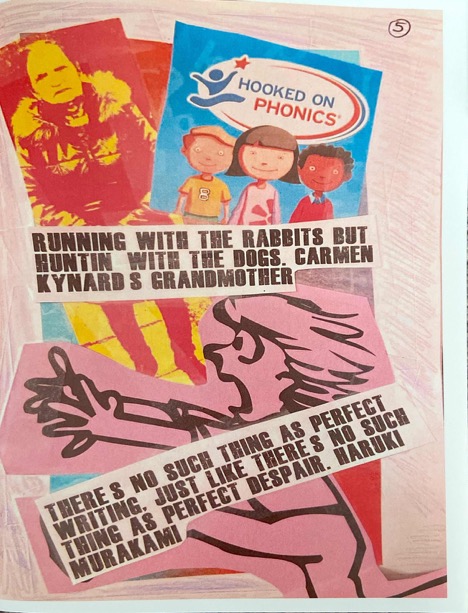

I’ve done all of the things people who zine do: read zines, order colorful paper and stickers, make plans to work with friends on a dope zine, etc. Yet I’ve never actually made a zine. If I was going to ask students to create a zine, I needed to make my own. The syllabus seemed like the perfect document to transform into a zine. Why? First, zines are community-facing publications (so are syllabi!). Second, zines are interactive, making room for readers to participate, continue the conversation (so should syllabi!). Third, zines refuse singular meaning. Instead, I can read a zine and interpret it in multiple ways at the same time. Or just as likely, I can experience it one way, and share it with a friend who experiences it in another. The syllabus can refuse singular meaning in similar ways. In the past, I’ve had students reflect on the course description at the beginning, middle, and end of the semester to think through context and meaning-making. Finally, Carmen Kynard has long modeled the creativity and possibility of syllabus-zines. And if Carmen Kynard does it, I wanted to too!

The process of creating a syllabus-zine was messy (7), but the outcomes were profound. On page 5 of the syllabus-zine, I provided my collage-response to “What writing means to me.” I then asked students to create their own collage-responses to the same question and insert them in the zine. I always hope students see themselves in the syllabi I create, but with this exercise, they literally saw themselves (and continue to see themselves as many of my students still carry around their zine with their personal collages).

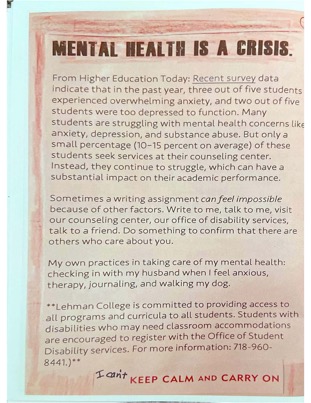

I also felt more comfortable inserting personal experiences in this syllabus zine, perhaps because a traditional, institutional syllabi is not collaborative and does not make room for other ways of communicating ourselves and our teaching styles. On page 16, for example, is a whole page dedicated to mental health, something extremely important to me and my teaching philosophy.

2. What is a zine even?

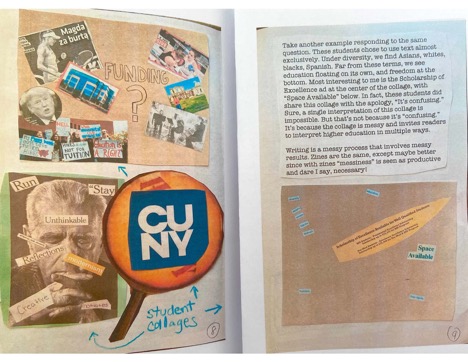

Though there’s a ton out there from Riot Grrrl zines to more contemporary #FreeCUNY zines, there’s no single, stable definition of what a zine is. However, when I shared the group zine assignment with students, I was surprised to find their questions weren’t centered on finding a single meaning for zines. Rather, students wanted to understand how a zine could possibly intersect with academic writing. In other words, how can a zine make room for the kind of writing and critical thinking I expected? To respond to these questions, I created another zine about zines. I was worried that this kind of response would become too abstract (too messy) and maybe make us all more confused. However, I paired the distribution of this zine with a list of rhetorical strategies. I asked students to find each of the items on the list within my zine. The list included items like, “Collaborative Writing,” “Call to Action,” “Historicizing,” and “Aesthetic Vibe.” Students were quick to point to examples of each item in my zine, but more importantly, consider how these examples were connected to our traditional conceptions of academic writing.

For instance, when a student pointed to pages 8 and 9 of the zine as an example of collaborative writing, another student commented collaborative writing was “the same as citing outside sources except you actually know the person.” Her comment led to a larger conversation about what we mean when we say “outside” sources and whether zines make room for “inside-outside” sources. That is, sources that are not our own words, but that come from our community so feel more inside, and maybe even more important to cite.

3. Will you trick us in the end and grade us harshly?

The group zine was worth 15% of their grade. Originally, I was going to create a list of 25 rhetorical strategies (have a vibe, use humor, use history, etc.), share the list with students, and ask that they try to incorporate at least 15 items on the list into their zine. However, my FIG mentors challenged me to think of a more collaborative assessment practice. After all, if the purpose of this project was to center collaborative learning and writing, why not also work with students in designing a method for grading the assignment? We’re currently still in process of developing our assessment strategy. During our initial brainstorming session, students brought up an important point, “How can we know what should count more or less if we haven’t actually finished publishing the zine?” Another student wondered if we should develop an assessment tool that was entirely community-centered. As in, students distribute their zines to the communities they were meant for and ask members of this community to provide feedback.

I know zines don’t work for everyone, but I’ve learned that in trying to implement a collaborative assignment that scared me, I made room for messiness and failure, and in making room for messiness and failure, I [think] I became a better collaborator and teacher.

Notes

[1] Though the initial theme/purpose of my posts centered diversity, I’m a little fatigued by the way diversity has become deployed as of late, so am trying to use inclusion/inclusivity as hopefully a more intentional alternative.

[2] Composing in Stages: The Effects of a Collaborative Pedagogy by John Clifford

[3] “Collaboration and psychological ownership: how does the tension between the two influence perceived learning?” by Avner Caspi and Ina Blau from Social Psychology of Education, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11218-010-9141-z.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banking_model_of_education

[6] Margot Mifflin offers a great overview of zines and punk rock girl culture https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1995-11-26-9511260414-story.html; Amy Wan also offers a great overview of zines in the classroom: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20709995

[7] I cut, pasted, and trashed at least six “first pages” before realizing I needed to work from the inside out. A lesson I think applies to all kinds of writing.

Dhipinder Walia is a PhD candidate in English and teaches English Composition, Creative Writing, and Asian/American literature at Lehman College, CUNY.

Leave a Reply