By Jessica E. Brodsky and Dr. Patricia J. Brooks

College students frequently turn to the Internet to find information as part of their academic and personal research. This is not surprising, given the rich diversity of resources available online. However, there is growing concern that most students lack the necessary skills to distinguish reputable news from fake news (i.e., deliberate misinformation spread through the Internet and other news sources), and they may not know how to accurately assess the credibility of what they read online.

The Stanford History Education Group has conducted extensive research on how today’s middle school, high school, and college students evaluate the information they read online (e.g., McGrew, Breakstone, Ortega, Smith, & Wineburg, 2018). Unlike expert fact-checkers, students rarely read laterally, meaning that they rarely leave the initial website to verify the information and learn more about the individuals or organizations behind the story (Wineburg & McGrew, 2017). Instead, they prefer to read vertically by scrutinizing the information for clues about its credibility. Unfortunately, looking closely at a website or an image is hardly a fool-proof strategy for determining whether the information is trustworthy.

At the College of Staten Island, CUNY, we have been working with a group of instructors in COR100, the College’s general education civics course, to teach students to read laterally. The College of Staten Island is one of several institutions across the nation that took part in the Digital Polarization Initiative (DPI), an effort by the American Association for State Colleges and Universities to teach college students the strategies of expert fact-checkers so that they can more effectively and efficiently assess the trustworthiness of online information. The four moves of expert fact-checkers (Caulfield, 2017) taught in the DPI curriculum are summarized by the acronym SIFT: Stop, Investigate the source, Find better coverage, and Trace claims, quotes, and media back to the original context.

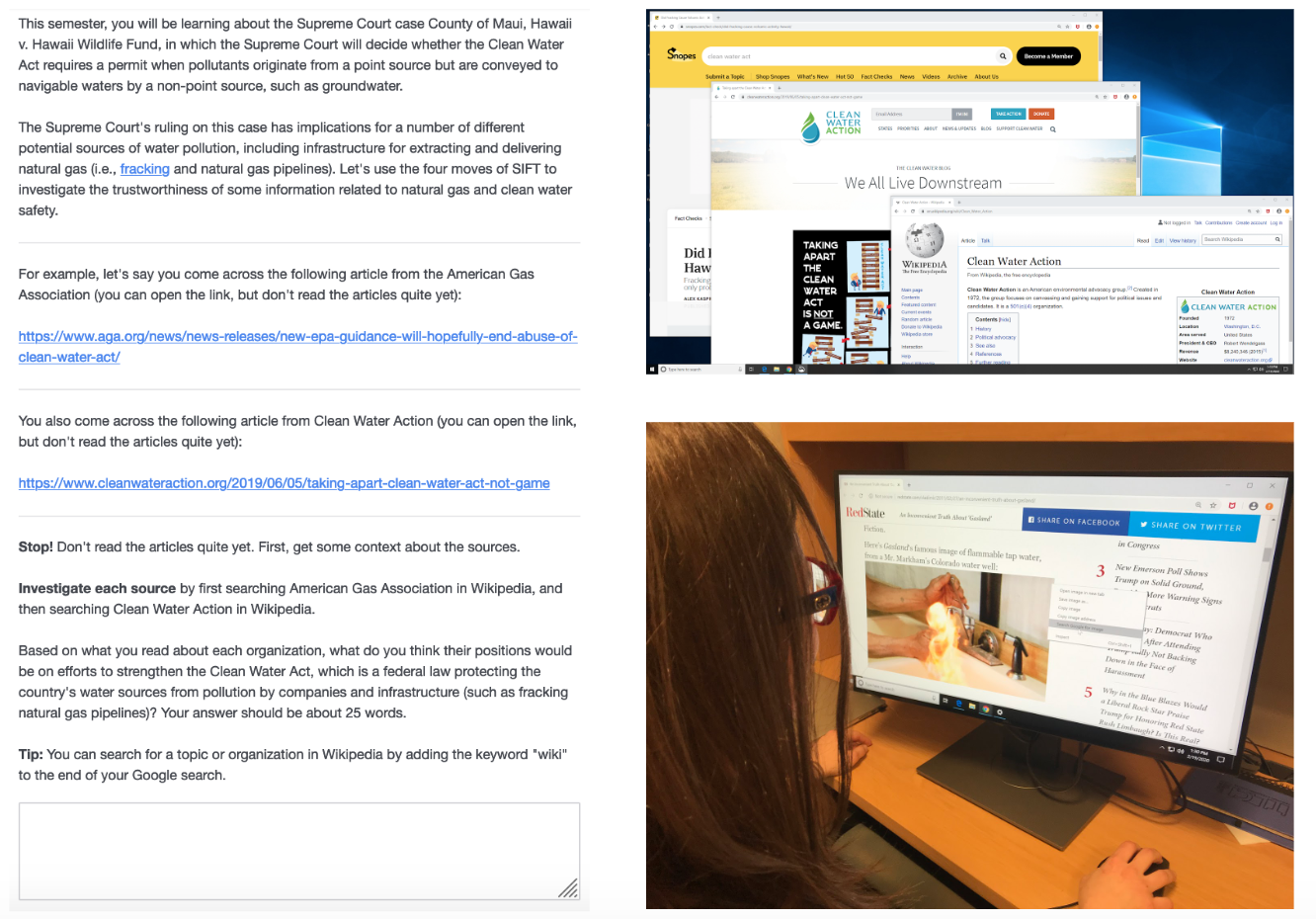

Each semester we have created a series of scaffolded, online assignments that align with current events discussed in COR100. In Spring 2019, students fact-checked articles, social media posts, and images about impeachment, immigration, and Amazon’s efforts to build a second headquarters in New York City. In Fall 2019, students fact-checked articles, social media posts, and images related to three Supreme Court cases. As part of each assignment, students watched brief videos reminding them about the SIFT fact-checking strategies, responded to fact-checking prompts, and received feedback on their responses. Figure 1 shows an example homework assignment from Fall 2019 on the United States Supreme Court case “County of Maui, Hawaii vs. Hawaii Wildlife Fund”, with screenshots illustrating how to investigate the source and how to trace an image to find the original context.

Figure 1. Left-side: A portion of a homework assignment asking students to do online research on a pending United States Supreme Court case that challenged the Clean Water Act. Top-right: Lateral search involves opening up multiple browser windows to investigate the source and find out more about the organization behind the news story. Bottom-right: Students practiced tracing an image back to an original context by reverse-searching for the image in Google.

Our close collaboration with the COR100 faculty has played a key role in the success of the DPI at the College of Staten Island. By drawing intentional links between the fact-checking curriculum and civic reasoning about current events, we are able to make the lessons more relevant to students’ lives and their development as informed citizens. Below are some reflections from faculty whose classes at the College of Staten Island participated in the DPI.

“Since having the opportunity to participate in the DPI, more of the students have begun to see how the media can construct the narrative of the daily stories they are exposed to. The students have expressed being more focused on scrutinizing the material put out by the media rather than accepting it based on face value.” – Patrice Buffaloe

“I was very happy with the response from the class. They generally agreed that we should look to the source of the information from the start, that the internet can be very misleading at times.” – Michael Matthews

“It is especially difficult for first year college students when they are tasked to research and cite trustworthy sources. The Digital Polarization Initiative, with its clearly defined skills methods, has vastly improved my students’ awareness of how to determine fact from fiction and to evaluate a source for hidden biases.” – Donna Scimeca

“I have found using the Digital Polarization Initiative pedagogy to be quite useful in helping students navigate the overwhelming amount of information provided by internet access. Getting them to pause and think first about sources, and then giving them the fairly simple tools to quickly verify the information provided by those sources, is crucial to their development as both students and citizens.” – Michael Batson

“The challenges students today face trying to navigate the social media and web based information landscape is frustrating to them and can lead them to zone out of the news and not care. Giving them skills to help them in this area often allows them to zone back in and actively engage with, rather than passively receive information. Each semester I find myself believing that this is some of the most important work I have ever done.” – Peter Galati

References

Caulfield, M. (2017). Web literacy for student fact-checkers… and other people who care about facts. Retrieved from https://webliteracy.pressbooks.com/

McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., Smith, M., & Wineburg, S. (2018). Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theory & Research in Social Education, 46(2), 165–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320

Wineburg, S., & McGrew, S. (2017). Lateral reading: Reading less and learning more when evaluating digital information. Stanford History Education Group. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3048994

Jessica Brodsky is a doctoral student in the Educational Psychology Program at the Graduate Center. Patricia Brooks is Professor of Psychology at the College of Staten Island and The Graduate Center.

Leave a Reply