by Angela LaScala-Gruenewald

Author’s note: This blog post would not have been possible without the anonymous input of students. All credit goes to the students in my Introduction to Law and Society class at John Jay College (Fall 2024). I have quoted them directly whenever possible.

For me, Fall 2024 felt like the semester AI really moved from the margins to a major part of the college classroom. What used to be a handful of students using AI for writing support became a broader reliance on AI. There’s a specific existential dread in realizing, mid-grading, that much of what you’re reading feels like robot writing. And it’s not just a few sentences but an entire paper, front-to-back. I love writing and admire the cadence, sharpness, and playfulness of college student writing, especially as you hear students sort out their voice over the semester. That made this shift disorienting, if not a bit sad. While the corporate consolidation of power in higher ed is nothing new and AI has been around for decades, large language models (like ChatGPT) and the promises of widespread (if inequitable) access, speed, and precision have taken AI to a new level.

Going into the fall semester, I assumed some students would use AI. From past experiences with plagiarism and technology use in class, banning or punishing AI use would not align with my values or abolitionist teaching principles. I tried two approaches that I thought might help students engage with AI. First, I added some extra writing warm-ups and free writes so students could work through class materials, scaffold papers, and develop their voices. I wondered how free writing would translate to their longer paper assignments. Would I even notice if they used AI? Would it matter if I did and they were still learning and engaging with class materials? Second, I added guidance for using AI in their papers. Students had to include a short explanation in their bibliographies explaining when and how they used AI. We talked about this policy during our syllabus ratification. My hope was that if they used AI, this would give them a moment to reflect on how it shaped their writing practice.

Sixteen weeks later these very imperfect approaches and, more significantly, my students, taught me several lessons. About 10% of paper’s included a short statement on AI use. Over the semester, I copied down these reflections and identified some themes. I also asked the class to do an anonymous, voluntary survey on AI, and a third shared their thoughts.

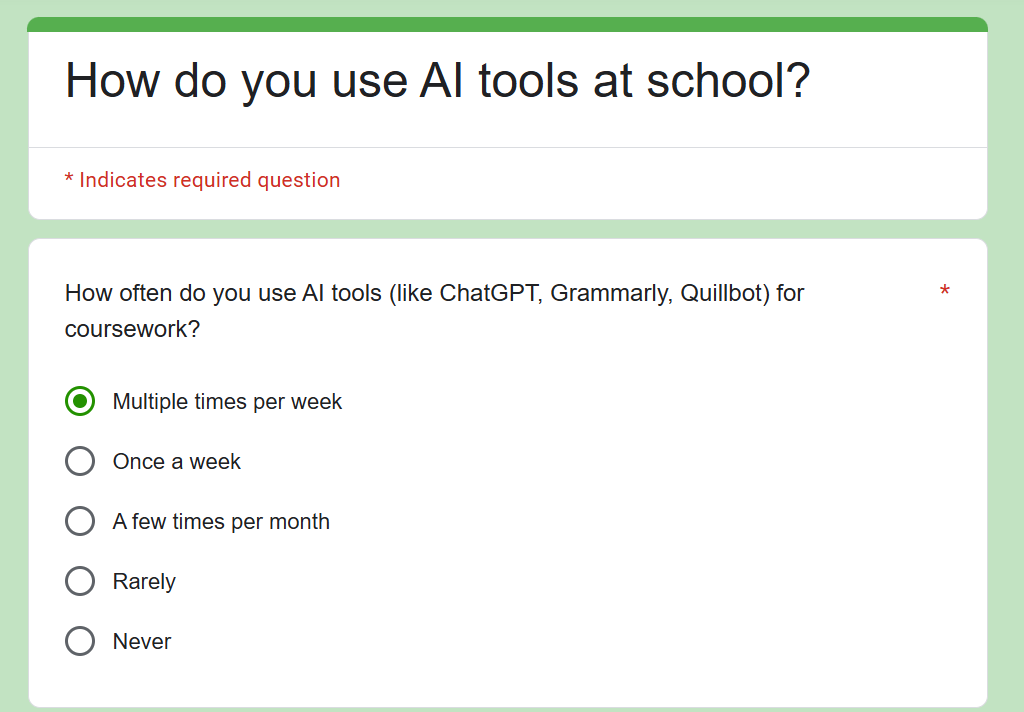

Screenshot of Google Form survey taken by author

Here are some of my takeaways from students’ papers and the survey.

Students use AI a lot: While 10% of my students disclosed AI tools in their papers’ bibliographies, in the survey, 75% said they used AI multiple times a week to complete school work. Only 8% said they never use AI.

Students use AI strategically: Students shared they used AI in their formal writing “as a formatting tool to organize how I wanted to convey my ideas,” “to form an outline,” “to start up ideas on how to begin each subparagraph,” “to create ideas on how to begin each topic,” “to ensure that my work is clear,” and “to check my writing for any mistakes.” Additionally, at the end of an autobiographical reflection on a friend’s death, one student wrote: “I used quillbot and Ai paraphrasers to make my statements more clear and concise as this is a hard story for me to share about my late friend.” AI offered a small buffer from the emotional labor of writing.

Taken together, these reflections reveal students use AI in ways that mirror the challenges of writing, especially in higher ed: (1) It’s hard to get started; (2) They are worried about grammar and formatting; (3) They want to make sure their ideas are clear. They know how important writing is as a communication device, but also how hard it is to get what is in our heads onto paper; (4) Writing is deeply personal. It can be both a vulnerable and generative space to process difficult topics. It can also be hard, scary, and slow. All four of these feel so relatable, a near perfect summary of the challenges of writing. Like, how amazing is this student’s take?

Honestly, what I’ve found most helpful about AI writing tools is how they bail me out when my brain just…stops working. You know those days? When you’re swamped, or stressed, and you just can’t seem to string a coherent sentence together? That’s when I turn to AI. It’s like having a brainstorming buddy who never gets tired. It helps me get those initial ideas down, or at least gives me a starting point when I’m completely blank.

Most students are cautious and critical consumers of AI: Students thought AI writing “sounds very robot-written,” “uninspired” (zing!), and “too simple.” Many recognize AI is only somewhat useful. One student wrote, “I really wish it was better at finding and giving me accurate resources” and they’d like it to “Really double-check its facts.” They saw AI’s flaws and ultimately felt responsible for shaping how AI is used in their work. There were exceptions here. Some students did have a hard time identifying AI’s issues. One student shared, “There’s nothing about AI tools that it’s least useful [for]” and noted it gives more “depth” and “voice” than Google. Few discussed concerns about data or ethics.

AI is predatory and extractive by design: When I was a writing tutor at Kingsborough Community College as part of their WRAC program, there was an ongoing issue of people hanging outside the college gates and offering to write students’ papers for a charge. This is a far more predatory approach to something that probably has existed since the beginning of time (read: grades). Finishing someone’s homework in exchange for something is in any school-aged kid’s playbook. AI’s free version promises to democratize one of the oldest tricks in the book. AI may be extractive, reify bias and inequities, and defeat the power of writing (like knowledge production); however, facially, it offers a sort of fast, sort of free freedom from the work’s pressures (a tireless brainstorming buddy).

In my own research, I think a lot about how neoliberal governance and structural racism translate into everyday practices and shift blame and burden onto people. Wendy Brown’s Undoing the Demos (2015) concept of responsibilization and AI strikes me as a good fit for understanding AI and this duality of freedom and oppression. Daniel Cryer, a professor of English, already wrote about it in relationship to AI and academic integrity, so I’ll share his words here, quoting Brown (2015,133-4):

Responsibilization refers to a pattern where tasks born by the public, the state, or some other large and powerful entity are offloaded onto individuals, often in the name of “freedom,” but without the authority or large-scale power that previously came with these tasks. [It] is “the moral burdening of the entity at the end of the pipeline [of power and authority]. It tasks the worker, student, consumer, or indigent person with discerning and undertaking the correct strategies of self-investment and entrepreneurship for thriving and surviving”…More succinctly, it’s part of the “bundling of agency and blame” that defines neoliberalism.

When it comes to AI, college students must grapple with a host of new freedoms and possibilities, and simultaneously balance the responsibilities of using technology safely and ethically. They are up against the biggest corporations in the world. As I think about this tension between freedom and oppression (and try not to make myself responsible for AI either), I have been wondering how I can move from the lessons my students taught me to some solutions for future classes.

A few ideas I’m thinking about:

Spend time talking about AI and encourage critiques. Don’t do what I did and mention AI once or twice. Revisit AI policies throughout the semester. Tie AI into class concepts, theories, and epistemologies. As bell hooks (1994, 147) reminds us in Teaching to Transgress, “Education as the practice of freedom is not just about liberatory knowledge, it’s about liberatory practice.” Many students already understand AI’s limits way better than I do: They are critical consumers. I want to make more space in my class for that knowledge and continue to make critique, as bell hooks would say, a “habit.”

Build collective power: In the classroom, syllabus ratifications, collaborative class policies, contract grading, and other forms of shared governance feel as important as ever and can open up early conversations about AI tools. These approaches can also dismantle traditional assessment systems that may lead students to rely on AI. On a broader level, resisting responsibilization requires collective practices beyond the classroom (like networks of care, resource-sharing, and class-struggle unionism). AI feels like another reminder to me of the importance of organizing, as AI represents just one piece of a broader set of logics shaping U.S. higher education.

Experiment with multi-modal learning. Academic norms can make writing rigid and exclusionary, and AI is largely trained to replicate formulaic writing. While I can’t undo students’ prior experiences with writing in a single semester, I can support learning through experiential, play, and place-based projects. I think writing is important, joyful, and an important skill, but I need to mix it up. We can learn in all sorts of ways and maybe that’ll help us–when we eventually feed something into the AI algorithm–to see and cherish how we, as humans, offer something unique. Then, those unique bits are what we can write down and hold as our own.

This last point is the other takeaway of students acting as cautious consumers. Cautious consumers mean students recognize that they are unique producers. I see my role as helping them continue to claim that power. That, I believe, is what ultimately will support student writing.

Citations

Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Zone Books, 2015

hooks, bell. Teaching to transgress. Routledge, 1994

Angela Lascala-Gruenwald is a PhD candidate in Sociology and a Fellow at the Teaching and Learning Center.

Leave a Reply