By Shima Houshyar

A few years ago, I was lecturing in front of a medium-sized classroom in an anthropology course at Hunter College. I was flitting across the room, furiously talking and writing on the white board. I was completely engrossed in the topic, but by the time I finished talking (ending with the classic novice teacher move, “Any questions?”), I was met with blank stares. It wasn’t that the students weren’t engaged or interested, but they seemed unsure where to even begin and were still processing all of the information that I had, in my excitement, lobbed at them. I decided to wait out the silence, but still no questions and more blank stares. It was at that moment that I realized: This isn’t working.

But what had happened? My explanations were simple enough, using everyday examples and language to make complicated concepts digestible.

Upon reflecting on the course and my pedagogy style, I realized, however, that I had chosen topics and modes of instruction that best fit my learning needs and had neglected to consider the learning experiences of my students. In other words, I had designed the course and the lesson for myself and not for the diverse array of student capabilities and knowledge bases present in the classroom.

I had, in fact, missed two crucial aspects of course and lesson planning: the principle of universality (and accessibility) and the principle of design. It wasn’t until I had learned about Universal Design for Learning (UDL) that I started to think of my course as a process of learning experience design and my audience as a diverse group of learners with unique skills, talents, and needs.

By applying UDL principles to my teaching, I was able to create a much more student-centered course and dynamic classroom experience. More importantly, however, following UDL guidelines will provide for a much more delightful classroom experience (for teachers and students). Fostering joy and pleasure in teaching and learning can be a powerful instrument to optimize learning, since students will be much more likely to care about the course material if they form affective attachments to the learning process. The communal pleasure of teaching and learning creates a sense of community and can open up radical possibilities for transformation of educator and learner alike.

What is UDL?

Universal Design for Learning is a set of guiding principles that aims to address the diversity of student needs by ensuring that our course and lesson designs are accessible to all students. By designing our classes in an inclusive way, we can create student-centered learning environments that enhance engagement, agency, and meta-cognitive learning (the ability to reflect on one’s own learning).

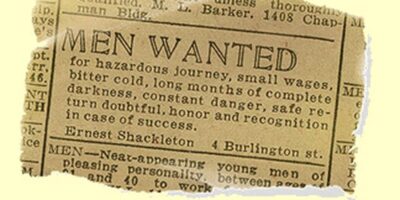

A brief explanation of UDL from Cast.org.

The three main UDL frameworks are:

- Multiple means of Engagement, which allows students to contend with why they are learning what they’re learning and to develop affective attachments to the course content

- Multiple means of Representation, which allows students to recognize and organize the content that they are presented with in a systematic manner

- Multiple means of Action and Expression, which enables students to contend with how they are learning, giving them meta-cognitive recognition

Visualizing UDL principles, adapted from Cast.org

The Principle of Universality: Accessibility is for everyone

The UDL concept emerges from the disability movement’s demands for accessible design in buildings and infrastructure, and applies these principles to teaching and learning. As radical activists have pointed out, designing structures and experiences for marginalized groups has the potential to provide access for a whole range of people with or without disabilities. A classic example in architecture is the provision of on-ramps into buildings for wheelchair users. But the on-ramp also helps people with bikes, strollers, or large deliveries. In pedagogy, providing a visual representation of a mostly text-based lecture or conducting a simulation, a hands-on exercise or experiment can help students who learn by doing or relate to the material in a more visual or tactile format better engage in the course material, but it can also deepen comprehension and retention for students who have facility with textual comprehension.

Making course material accessible is an ongoing process and cannot necessarily account for every mode of interaction with the material in the classroom or address every student need. Considering accessibility and universality, however, is still an important way to facilitate entry into the classroom for students. The ultimate goal of UDL is to remove barriers to learning for students, so that students have the agency, freedom of choice, and sense of empowerment to engage with the material on their own terms. For example, students can be given a choice between doing a more traditional essay assignment vs a more creative, visual presentation. This enables students to approach the material from their own interests and positions of strength, making them both care about the material and enjoying the process while doing so.

The Principle of Design: The power of good design

In The Design of Everyday Things (2013), Don Norman, one of the foremost public voices on design, writes: “Great designers produce pleasurable experiences” (10). While Norman is mainly writing about the design of modern technologies and objects, the same principle can be applied to teaching in the classroom. A good learning experience design is not just utilitarian but it can foster joy and delight in learning for both student and teacher.

And like all good design, we have to start at the end (also known as Backwards Design): what is it that we want students to get out of this semester-long experience? What goals do we want them to accomplish? What activities, materials, or assignments will enable them to get there? Bearing in mind the first principle of accessibility and universality, what barriers might students encounter that might prevent them from accomplishing these goals? How can I structure my course to lower those barriers to entry, such as presenting the material in different formats or giving options for assignments? And more importantly, how can I design my course in such a way that it fosters a “pleasurable experience” for both students and myself, opening up possibilities for mutual transformation?

How I incorporated UDL into my course

The good news is that many instructors already deploy UDL principles in their pedagogy without being aware of it. But by explicitly designing courses with UDL frameworks in mind, instructors can better help students achieve the course’s learning outcomes.

I decided to include a more creative assignment in my introductory anthropology course, asking students to conduct an ethnographic participant-observation of their workplace or another location of their choosing (with my approval). Each journal had a specific prompt that guided students on what to focus on while giving them a broad leeway on what to write.

Students were excited about the assignment but were unsure of what an ethnography should look like. So I provided them with excerpts from my own previous ethnographic projects, asking them to annotate it and come with questions and comments. This led not only to a great classroom discussion but it allowed students to view me not just as a teacher but also as a researcher that they could model. Models, whether from the professor or other students, are powerful tools for learning since they help shape students’ mental models of particular genres of writing or research methods. While some students wrote their ethnographies similarly to my format, others became more creative, writing in more experimental and expansive modes.

I dedicated several sessions of the semester for students to read and provide feedback to one another, thus creating a sense of community, since they were reading about each others’ real-life experiences. Students were able to connect their real world experience with the course material that we were learning, placing the reading within the context of their own analysis of the social world. Every time we covered a somewhat difficult concept or there was a lull class discussion, I was able to pull examples from students’ own writings, which helped spark more engagement and classroom discussion.

How else might I have made this assignment more accessible and enjoyable? Perhaps one of the journal prompts could have asked students to take “an ethnographic photograph” and to write one or two paragraphs explaining the social/cultural significance of what they had photographed and presented it to the class. This could have opened up valuable conversations about the politics of photography, visual culture, and representation while also giving students the freedom to engage with the assignment from their points of strength and interest. In fact, the possibilities of providing multiple modes of Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression are endless.

Pleasure and radical possibilities in pedagogy

By the end of the semester, three very important things had happened:

- Many students exclaimed how much they had actually enjoyed the process of writing their ethnographies, reading others’ writing and discussing them with one another. I too had thoroughly enjoyed learning about my students as individuals with lives outside of the classroom that nevertheless thoroughly intersected with the course material;

- I had taught my students the most important lesson that I wanted them to take away from the course in a way that a lecture would never have been able to convey: how to turn a critical, social scientific eye on the world around them and become budding ethnographers of the everyday; and

- Learning to think in terms of universal design had transformed me as an instructor, teaching me to always center student agency, choice, and accessibility in all my courses moving forward.

The framework of Universal Design for Learning pushes educators to design with their students’ needs, skills, and talents in mind. Good and accessible course design not only helps students engage with the material on their own terms but it makes the process a pleasurable one, thus opening possibilities for mutual transformation.

———-

Shima Houshyar is a doctoral candidate in Cultural Anthropology and a TLC Fellow.

English Prof

As an ESL teacher, your journey with UDL really struck a chord. Moving from lecture-heavy sessions to creating space for student voices and engagement is transformative—for both teacher and learner. The ethnography assignment was a brilliant touch, blending academic rigor with personal connection. It’s inspiring to see how thoughtful design, grounded in inclusivity, brings out the best in students and fosters a classroom culture of joy and mutual growth. Thank you for this insightful share—it’s a lesson in the power of purposeful, student-centered teaching.