By Cristina E. Pardo Porto

For me, teaching a language means teaching students to create something (words, sentences, expressions). Since I started teaching Spanish language and cultures at CUNY, informed by my background as a photographer and a poet, I have been concerned with understanding the language learning process as a creative and material interaction with something that requires shaping: transforming language into words is always a creative moment. When we learn a language, we bring to the classroom myriad forms of knowledge that, ultimately, will take shape in other registers (written, oral, visual). As a teacher, my goal is to frame language learning through the lens of creativity.

Building on the philosophy of “writing-to-learn” that I encountered as a Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) Fellow, I have been reflecting on an approach of creating-to-learn, which blurs the boundaries between teaching content and teaching skills. In this sense, I understand teaching and learning as a shared, collective process that requires deep reflection through doing and making things. Instead of just delivering information, in my classrooms I always seek to

- boost hands-on interaction with the content of the lesson

- foster imagination through collaboration

- build community through using and sharing materials

- forge interdisciplinary connections

I do so with a project-oriented methodology and experiential learning activities. I would like to share one example that illustrates this methodology of creating-to-learn. As a final project for one of my advanced Spanish language courses for Latinx students (heritage speakers of Spanish),* my students made and painted cartonera books by hand.

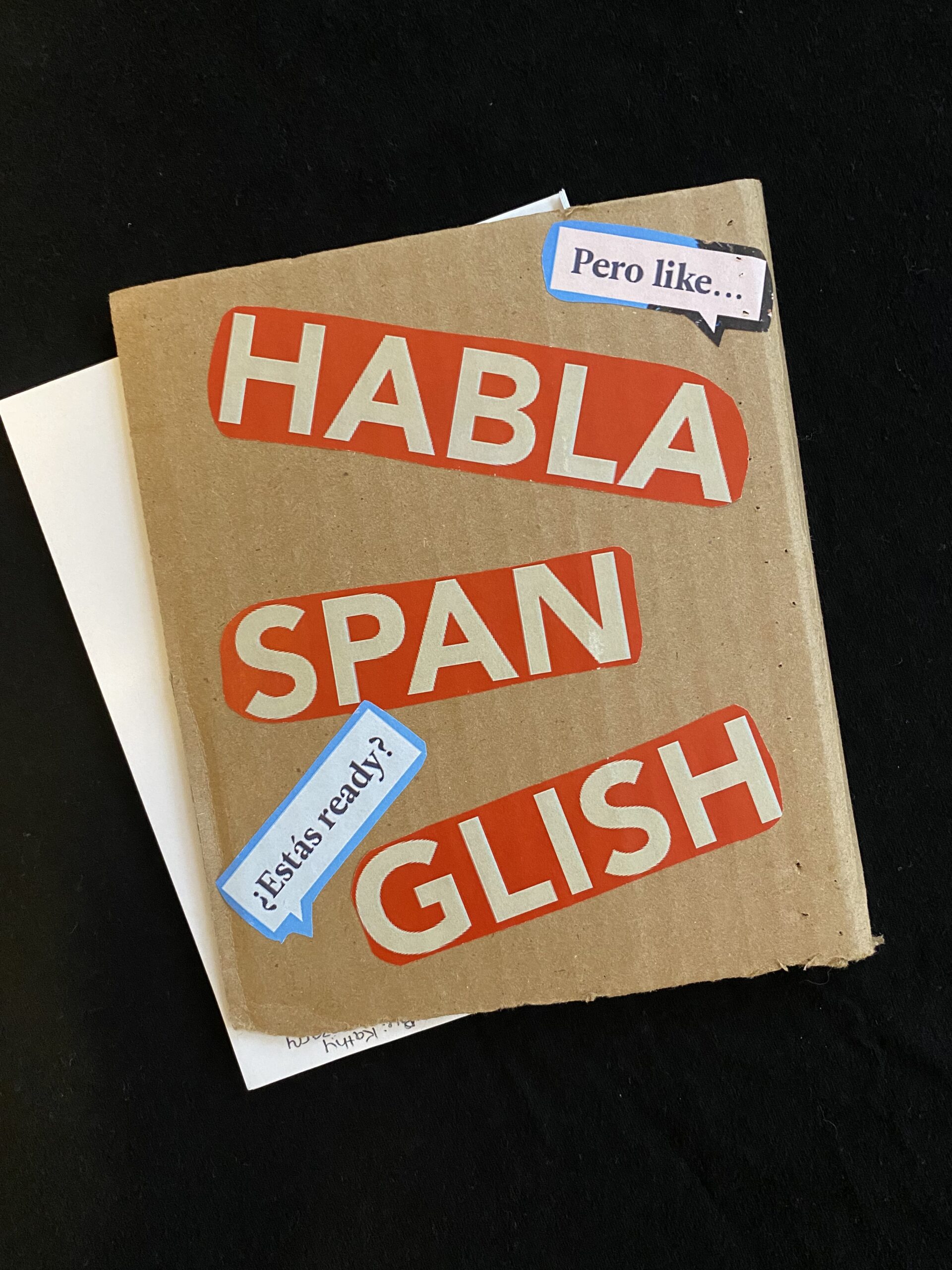

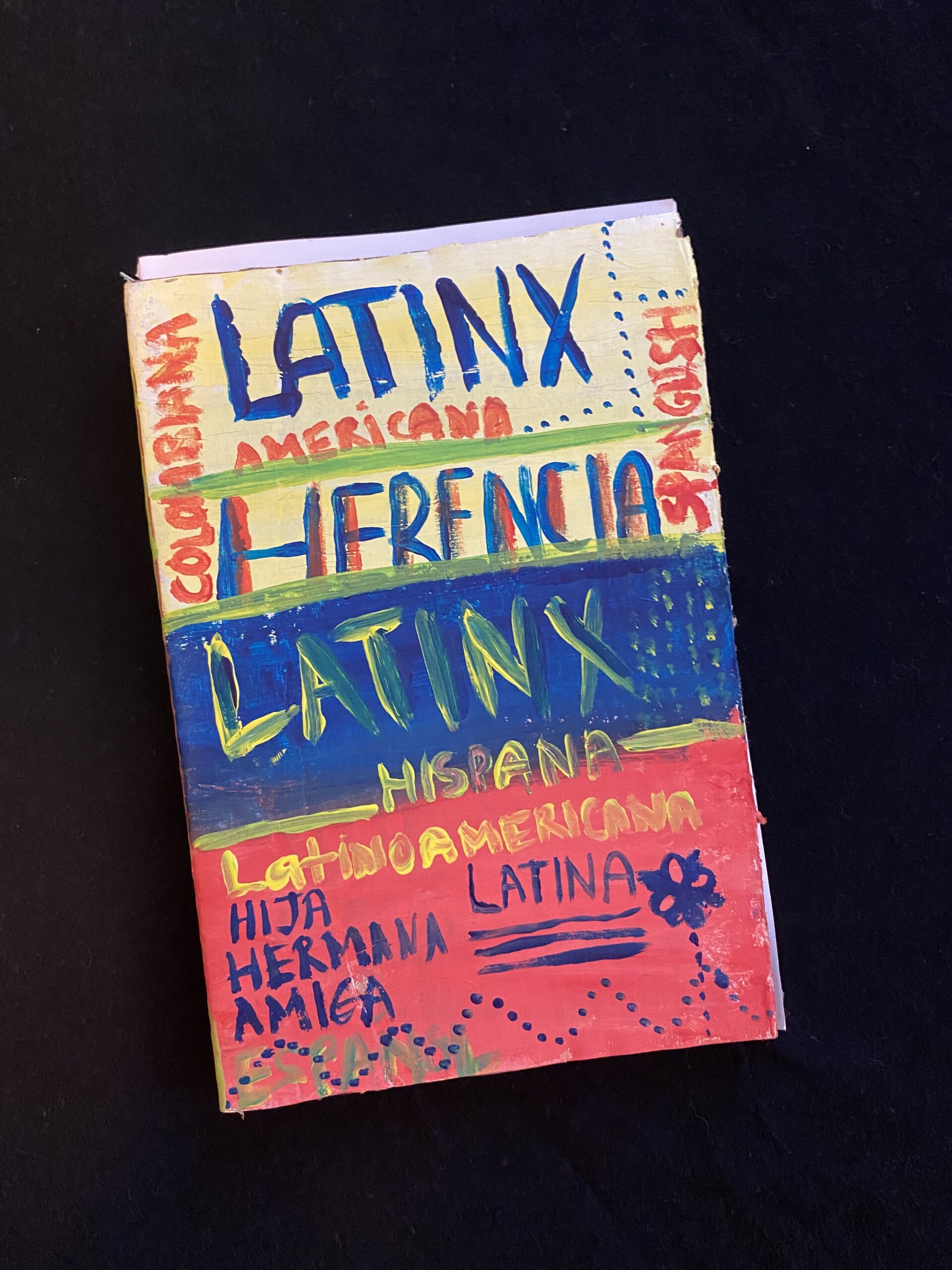

Cartonera book that one of my students made. (Photo by author)

Cartonera book that one of my students made. (Photo by author)

Cartonera books are part of a large artistic and activist publishing movement that was formed in the early 2000s in Argentina, a movement that has now spread through all Latin America and beyond its borders. This movement was founded by the underground editorial group named Eloísa Cartonera. This group of poets and writers got together to reflect on other ways of publishing in response to the devaluation of the Argentine peso and the economic crisis that followed it. This crisis increased the number of cartoneros – peoples that made a living by collecting and selling recycled cardboard and other waste materials. Eloísa Cartonera and other groups started making and painting book covers with these cardboards, home-printing very small batches of book editions, and selling them at very low prices (just the cost of production). It was common that the production, painting, and printing of cartonera books involved the local communities in book-making workshops and community fairs, and the distribution was made through small cooperatives. With this initiative of the cartonera movement and with an activist impulse, writers wanted to democratize the access to literature and promote literacy among a greater public, eliminating the socioeconomic barrier that the crisis brought to the literary scene.

Cartonera books on display at Eloisa Cartonera, 2019. (Photo by author)

I visited the headquarters of Eloísa Cartonera on my visit to Buenos Aires in 2019. (Photo by author)

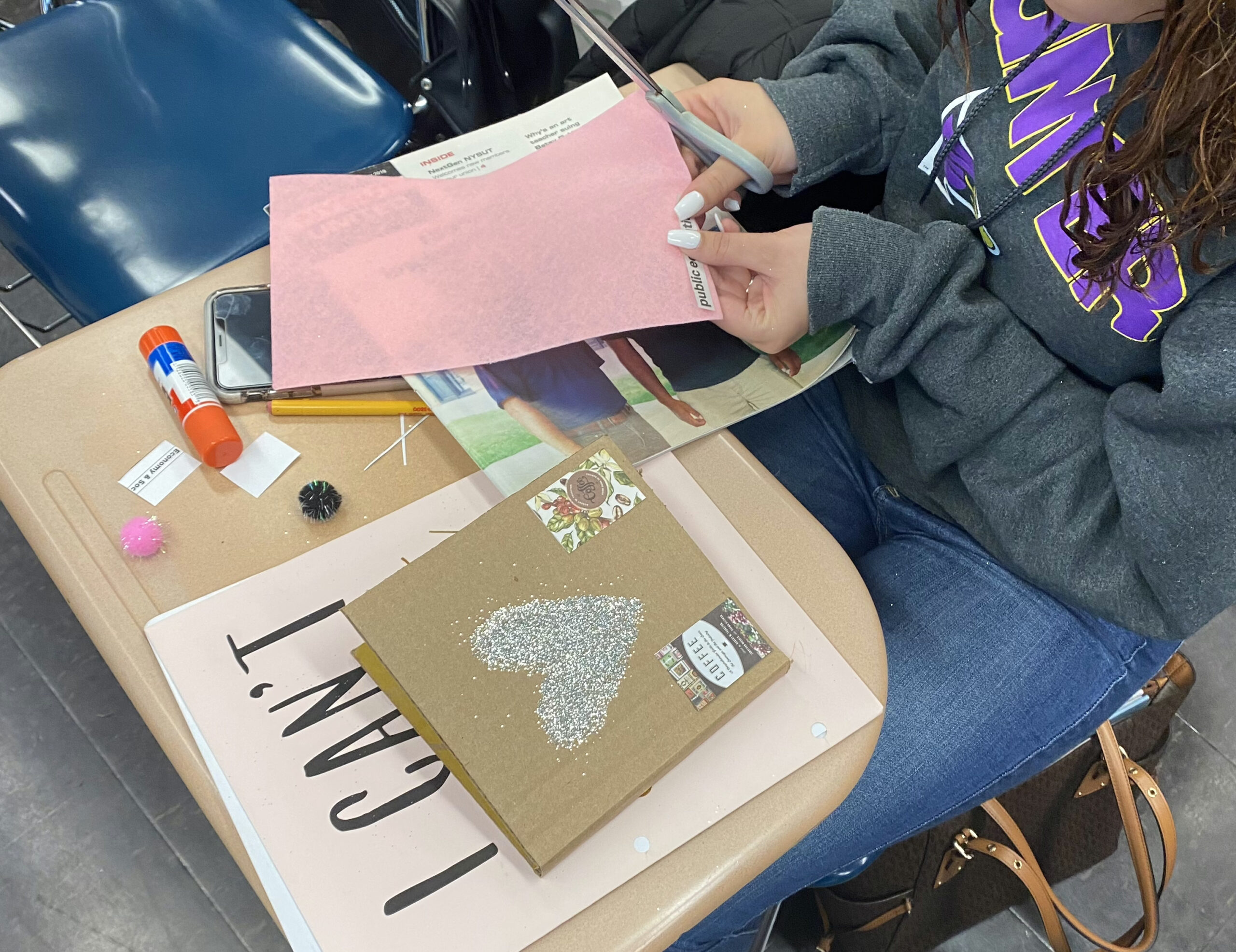

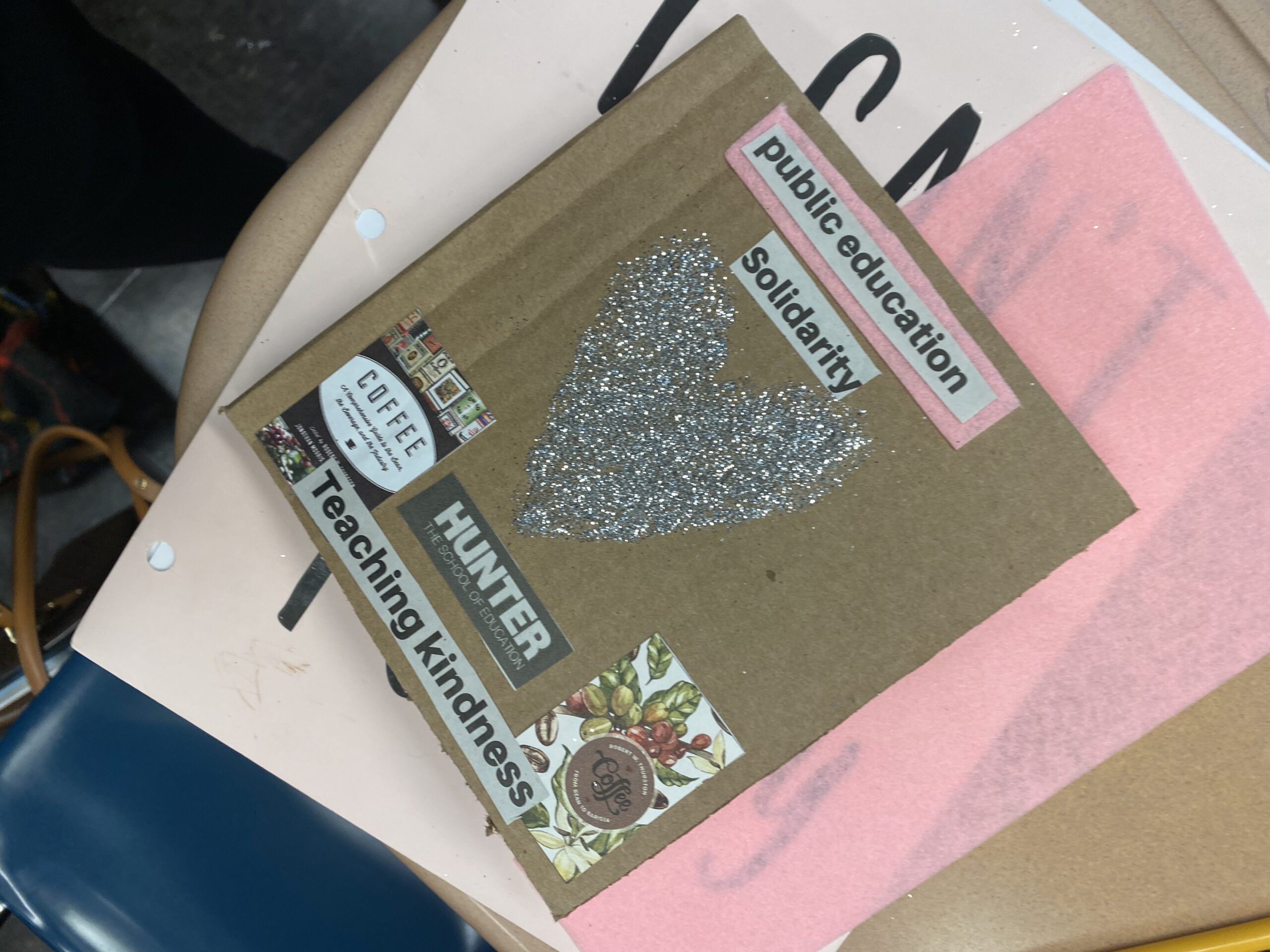

I wanted to emulate this collective experience and reflection around literature and access in my classroom and, at the same time, reflect on language diversity, eco-friendly practices, and community building in times of crisis. I asked my students to find cardboard (like the many Amazon boxes we see on the streets) and bring them to the classroom, along with paint, crayons, scissors, glue sticks, old magazines, and other art supplies they already had at home. After sharing with them what cartoneras are and their history, we made and decorated cardboard book covers during class time.

As part of a graded component of the course, students completed low-stakes writing assignments that were scaffolded during the semester and led up to this final cartonera book project. In these short writing pieces, they reflected on the different Spanish-speaking communities in the US –that are their own communities– in relation to immigration stories, language diversity, and Hispanic identities through storytelling. For example, one of these pieces asked students to interview a family member about their migration story that brought them to the US. Some students reflected on their complex and identities as Latinx youth in public education, while others reflected on their journeys of re-learning a language they already knew. Afterwards, we shared our hand-made books and stories with the rest of the college community.

A cartonera book in progress. (Photo by author)

Making cartonera books in class with my Hunter College students. This student is an Education major and wants to be a Spanish teacher in the future. (Photo by author)

With the design of this project, I provided my students with the opportunity to participate in several learning modalities and to practice different forms of literacy by creating a cartonera book. Nevertheless, creativity or creative assignments are not only related to art-making.

I invite you to approach creativity in a broader sense, and to include other possibilities for creative and hands-on assignments in your classroom. For example, you could:

- Reformulate the traditional oral presentation: have your students create their own activities and games, or moderate a session with questions of their own design.

- Ask students to take photographs (related to the content of the class) and bring them to the classroom to discuss them as part of a lesson.

- Try other modes of writing: Free, collective, poetic…

- and other modes of interaction (like role-playing and peer-review activities)

- Create DIY artifacts together: collages, brochures, objects, robots…

- Integrate participatory technology and visual tools in final projects, such as creating video presentations and hosting a watch-party for the last day of class.

- Interact with the classroom and the college space: use the walls to create a gallery-like space to display content, text, and visuals.

- Bring your students’ hobbies and extra-curricular skills (i.e crochet, sports, programming, acting, cooking) into the class space and propose an activity where they take advantage of these.

Why should we push for this? Boosting creativity in our classroom has many positive outcomes. In introductory courses, it may help by activating previous knowledge and welcoming stimulating connections and reactions. In more advanced courses, it provides students with the opportunity to engage critically and materially with the content of the course. In seminars, it enables students to forge complex interdisciplinary connections. Creativity will always lower the pressure the students feel towards exams, presentations, and oral participation (ideally, we should incorporate these components into a creative assignment or project). And, ultimately, it’s always fun to “create” something with our hands in a collaborative environment.

What should we take into account while assigning creative assignments? There is a prejudice that art-making is related to “kids’ games,” so we want to avoid that students feel infantilized and make sure that they feel taking advantage of class time. Also, not all of us possess an inclination towards arts and crafts. In my experience, these prejudices last just the first couple minutes of the activity. I encourage you to bring the full potential of creating-to-learn by framing it with critical and place-based pedagogies. Creativity is part of our daily life, even though we are not fully aware of it.

Cristina E. Pardo Porto is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures and a TLC Fellow.

*Heritage speakers of Spanish are students that are already fluent in Spanish language (passed affectively through their families), but haven’t had a formal education on the language. It is worth noting that these students may bring many insecurities to the classroom, in relation to dominant language ideologies imposed on them, their language proficiency, their bilingual identities, and their personal experiences as first- generation students coming from Hispanic communities formed through immigration.

Leave a Reply