By Jessica E. Brodsky and Dr. Patricia J. Brooks

Media literacy is defined as the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act on online information (e.g., articles, photos, videos, social media posts; Hobbs, 2010). While today’s students are frequently described as “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001), their online experiences may be rather task-specific (e.g., games, shopping, social media), with wide gaps in their technical knowledge and skills. As college instructors, we simply cannot assume that our students will develop media literacy knowledge and skills just by spending time online. Being able to conduct a Google search is not the same as being able to judge the quality of the results. Posting to Instagram is not the same as considering how that post will be shared, altered, and potentially misrepresented by others.

Recent research points to critical gaps in college students’ media literacy knowledge and skills. When the Pew Research Center administered a ten-item digital knowledge quiz to over 4,000 adults, with items such as “If a website uses cookies, it means that the site …”, they found that adults between the ages of 18-29 and those with at least an undergraduate degree scored highest, but their median scores were still only five correct and six correct, respectively (Vogels & Anderson, 2019). You can take the Pew Research Center’s digital knowledge quiz here to see how you fare.

Similarly, in 2016, the Stanford History Education Group asked students of all ages to assess the credibility of online social and political content. They found that most students, including college students, rarely verified online claims or investigated the sources (i.e., organizations) making the claims, leaving them potentially vulnerable to fake news and misinformation (McGrew, Breakstone, Ortega, Smith, & Wineburg, 2018). You can find examples of the tasks that students completed on the Stanford History Education Group website.

Ideally, students would acquire media literacy knowledge and skills before coming to college as part of their high school coursework. Unfortunately, however, the U.S. does not have a national media literacy curriculum, even though the need for this instruction at the K-12 level is widely recognized. In light of the upcoming presidential election, the Stanford History Education Group recently published a follow-up report which found that most students in a national sample of high school students performed poorly on tasks asking them to evaluate the credibility of online information (Breakstone et al., 2019).

Since students come to college with varying levels of media literacy, we must find ways to integrate media literacy instruction into college courses, particularly at the introductory level. The sooner students are introduced to these skills, the sooner they can start practicing them, regardless of their major. However, as college instructors ourselves, we recognize that introductory-level courses have a tradition of being content-focused and typically do not allow time for much skills-focused instruction. In addition, since introductory-level courses are often taught in multiple sections by different instructors, it can be difficult to unify instruction across sections. One way that we have found to address the challenges of integrating media literacy instruction into introductory-level course with multiple sections is through the use of scaffolded online homework assignments.

At the College of Staten Island, we have been using Qualtrics online survey software to create and administer homework assignments that instructors across sections of introductory psychology use to teach students the information and media literacy skills of finding, reading, and summarizing scientific abstracts. Through a series of online assignments featuring Content Acquisition Podcasts (CAPs; i.e., brief narrated PowerPoint slideshows; Kennedy & Thomas, 2012, see Figure 1), students learn about differences in the credibility of search results from Google and Google Scholar and how to analyze the argumentative structure of scientific abstracts. They also learn about best practices for avoiding plagiarism when summarizing other people’s work, including using Wikipedia to research jargon.

Figure 1. Students watched content acquisition podcasts about how to read (https://youtu.be/ZosurAYg6Jw) and paraphrase (https://youtu.be/iJDNRhhunR8) journal abstracts.

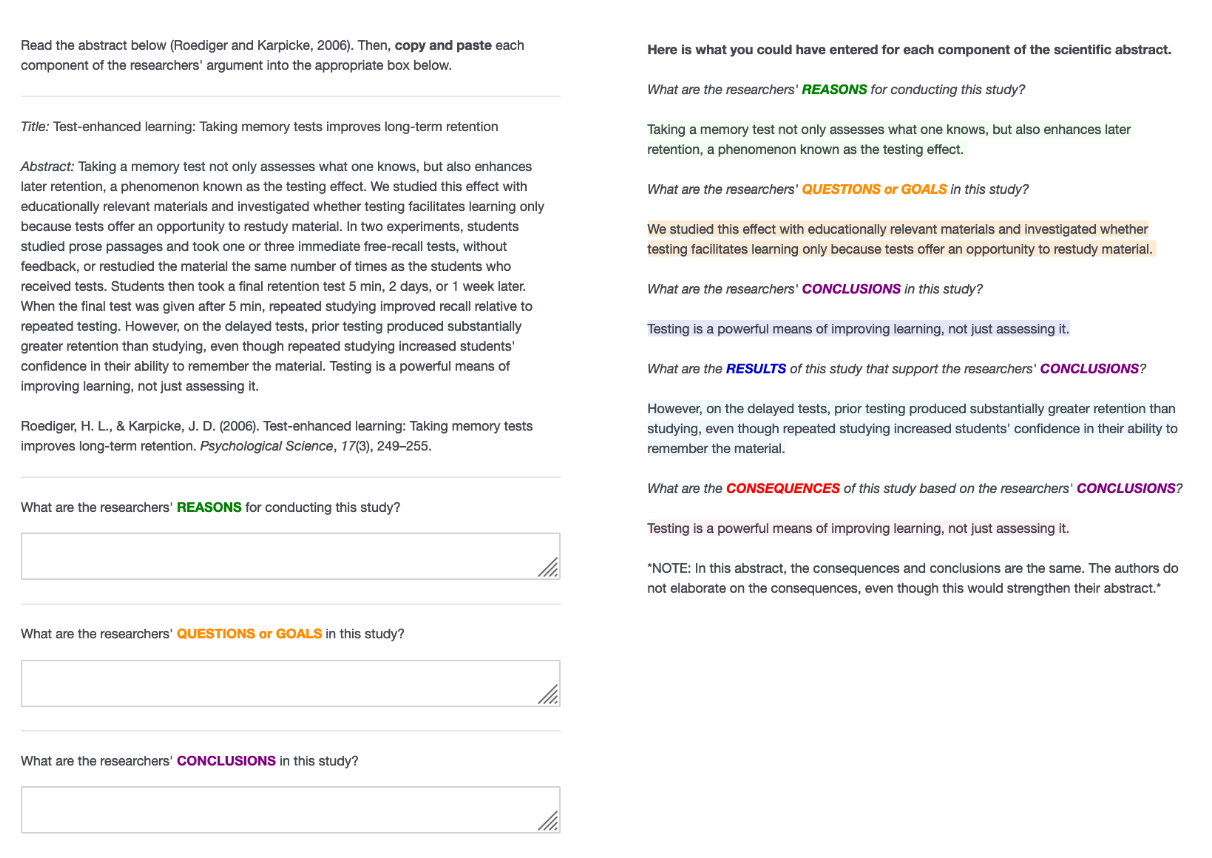

After watching the CAPs, students practice applying what they learned to reading and summarizing scientific abstracts related to topics covered in the course, such as the testing effect (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Students practiced identifying argument components in journal abstracts and received feedback on their work.

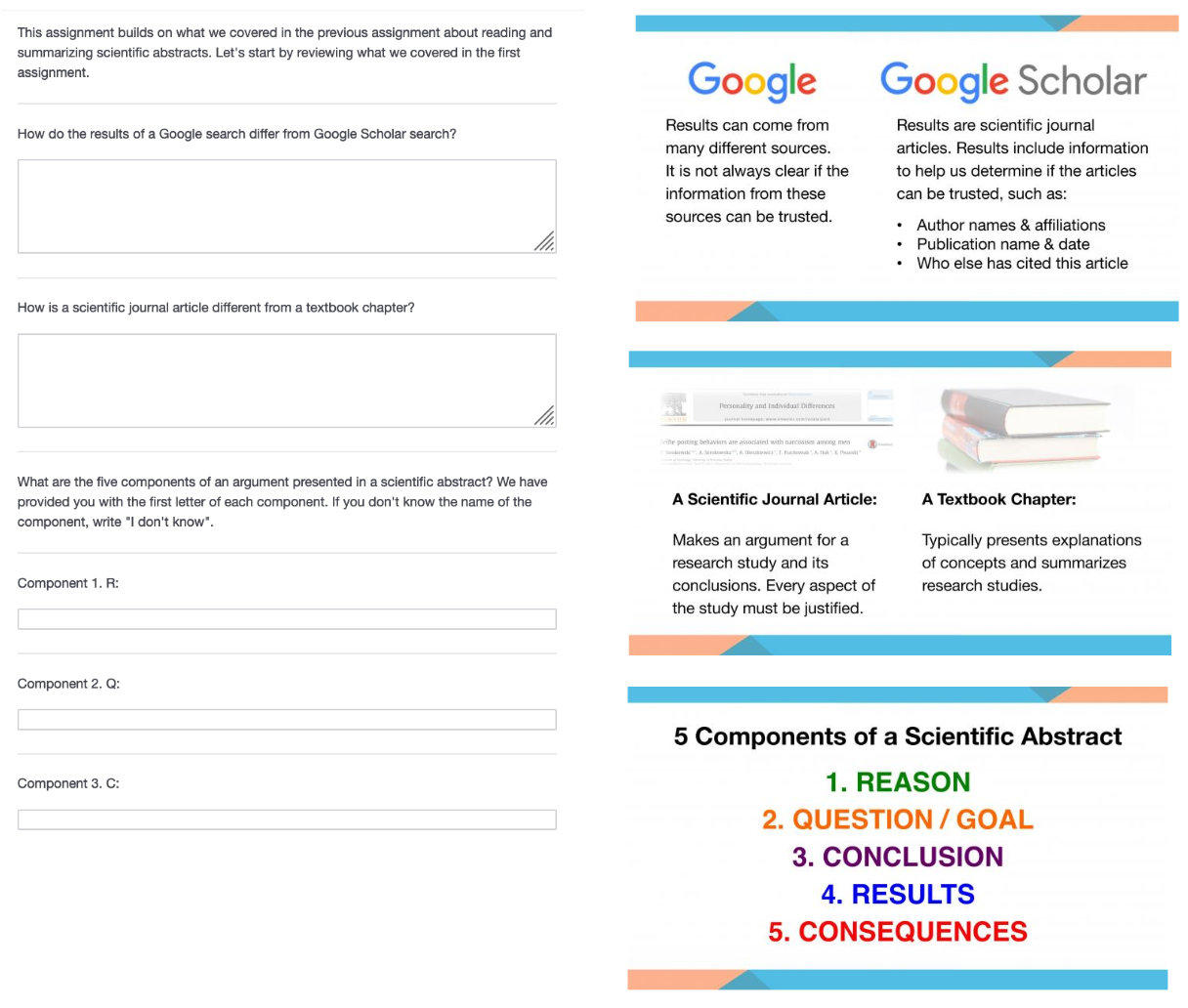

The assignments are designed to build on one another, with each assignment prompting students to review knowledge and practice skills that they learned in previous ones (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Students practiced recalling key information from previous assignments and received feedback on their work.

To increase instructor buy-in across sections, our online homework assignments have the following features:

- We provide each section’s instructor with unique links to each homework assignment to post in Blackboard. We send each instructor their students’ responses after each assignment is due and provide opportunities for students to make up missing work.

- To help instructors integrate these online homework assignments into their syllabi, we tie the abstracts used for each assignment to course content. We also end each homework assignment with a practice test, utilizing multiple-choice questions from previous departmental exams, so students can gauge how they are doing in the course overall.

- The assignments are graded as pass/fail, which reduces the grading load and establishes the assignments as low-stakes formative assessments of students’ skills.

These online homework assignments have the additional benefit of introducing our students to the process of learning online, a growing trend in higher education (Allen & Seaman, 2016). As part of these online assignments, students review material (via text or video), answer questions, solve problems, and receive feedback on their work. These components are similar to features of online or hybrid courses they may take at other points in college and beyond.

In our next post, we will describe our use of scaffolded online homework assignments to develop college students’ skills for analyzing and evaluating the trustworthiness of online information as part of the College of Staten Island’s general education civics course COR100 United States: Issues, Ideas, and Institutions. This instruction is part of the College of Staten Island’s participation in the AASCU’s Digital Polarization Initiative, a multi-institutional effort inspired by findings from the Stanford History Education Group to teach college students how to fact-check online information.

References:

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Online report card: Tracking online education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED572777

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Wineburg, S., Rapaport, A., Carle, J., Garland, M., & Saavedra, A. (2019). Students’ civic online reasoning: A national portrait. Stanford History Education Group & Gibson Consulting. Retrieved from: https://purl.stanford.edu/gf151tb4868

Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and media literacy: A plan of action. Washington, D.C.: The Aspen Institute. Retrieved from https://works.bepress.com/reneehobbs/13/

Kennedy, M. J. & Thomas, C. N. (2012). Effects of content acquisition podcasts to develop preservice teachers’ knowledge of positive behavioral interventions and supports. Exceptionality, 20(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362835.2011.611088

McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., Smith, M., & Wineburg, S. (2018). Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theory & Research in Social Education, 46(2), 165–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

Vogels, E. A. & Anderson, M. (2019). Americans and digital knowledge. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/10/09/americans-and-digital-knowledge/

Jessica Brodsky is a doctoral student in the Educational Psychology Program at the Graduate Center. Patricia Brooks is Professor of Psychology at the College of Staten Island and The Graduate Center.

Raoul

Congratulations Jessica and Patty. I eagerly await your next post.