by Ashley Marinaccio

I’ve been assigned a paper where I have to prove that a digital project I’ve been working on over the past year is scholarship. It’s a University formality, but I’ve dragged my feet for two months because I feel like writing a paper about this digital project defeats the entire purpose of the project standing alone as digital scholarship. It seems so obvious to me – of course, this is “scholarship,” just as film, theatre, fine arts and embodied ritual can be passed down generationally and can be considered a form of scholarship. What excites me most about this project is that it is accessible and will reach people outside of academia. We are producers and consumers of knowledge whether or not we are aware of it. The way things are changing politically and socially, as institutions (like governments and organizations) that we once put so much trust in are crumbling across the world, makes it evident to me that rethinking and expanding definitions of scholarship is imperative.

I come from a working-class background and didn’t really know that advanced degrees existed in the humanities until undergrad, so it’s really important to me to make work that’s accessible to people who are not in academe. My proposed dissertation research focuses on theatre in war zones. The more invested I am in my dissertation project, the more important it is for me to figure out how to translate the ideas, theories, and experiences on theatre in war zones to people who are not theatre practitioners, let alone academics. This idea truly hit home for me when my mother was dying and I was surrounded by the community I was raised in, many of whom are living paycheck to paycheck and trying to explain what I do in my Ph.D. program using the language that’s been established in my “45 second academic elevator pitch” has little relevance on their lives. I want to create work that speaks to the community I come from.

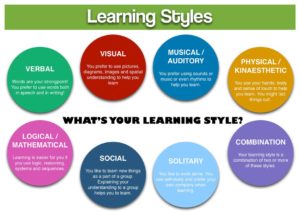

So, on this slightly self-righteous note, I have been trying to embrace this ideology in my teaching work, while also upholding expectations of academic rigor. We know that there are many ways students learn and it’s important to embrace several different learning styles in developing classroom curriculum because not everyone learns in the same way.

“What’s your learning style?” This chart illustrates the different learning styles we could consider developing classroom curriculum

As someone who learns best through a combination of verbal, visual, and social experiences, it makes sense to me that different learning styles are going to produce different forms of scholarship. I encourage my students to dig deeply into how they can create work that’s intellectually stimulating, but also accessible. In order to change the culture, we need to do our best as educators to embody and encourage students to take risks in their own studies and expand what we understand as scholarship.

I want to put this idea into practice by creating a web series about theatre for my final ITP (Interactive Technology and Pedagogy) capstone project, Stage Left, a web series that introduces audiences to the performances, artists, theatre-makers, and communities that are making work in places that typically go unnoticed by the mainstream. The purpose of this project is to engage audiences in community-based practices and applications of performance work that are not as visible as Broadway and regional theatre, to shift the narrative when it comes to the discussion about what theatre looks like in the United States. By highlighting the work of artists who are actively using theatre to engage, change and inspire their own communities, Stage Left aims to inspire artistic appreciation and activate audiences and viewers to get involved in their own community-based theatre initiatives.

Each episode of Stage Left features a new grassroots, community-based theatre, collective or organization and demonstrates how these local theatres are having an impact on their communities. Utilizing digital media to introduce audiences to the work of local theatre-makers including directors, actors, musicians, and creative staff, Stage Left provides unparalleled access to the voices and work of theatre-makers who do not regularly have voices in the mainstream theatre culture.

The first season of Stage Left covers the work of Cabaret for Life: a JerseyShore-based charity that puts on original dinner theatre productions about the local area to raise money for HIV/AIDS research; MAAFA (Kiswahili term for “terrible occurrence”), performed by the Incarn ministry at Mount Pisgah Baptist Church, a Brooklyn-based church collective theatricalizing the Middle Passage and trans-Atlantic slave trade; Tribe of Fools, a Philadelphia-based circus troupe that utilizes physical theatre to address pressing mental health issues in the community; University Settlement, the oldest settlement house in New York which provides artistic leadership programs for historically underserved communities; The Queens Theatre, a senior citizen ensemble (ages 65+) who are staging their life stories; and Eagle Project/ASHTAR Theatre, Native American and Palestinian theatre organizations who are collaborating to build solidarity around indigenous peoples’ stories .

I am really excited to be entering a Ph.D. program at a time where it seems folks are being more inclusive about what constitutes scholarship. I know it hasn’t always been this way. I have been extremely inspired by the conversations happening in ITP, and hearing about successful digital dissertations. I also am fortunate to have a team of mentors who are encouraging me to think about film as scholarship. I look forward to testing these ideas, making modifications, and seeing how this work can potentially impact audiences outside of the academy.

Ashley Marinaccio is a Ph.D. student in Theatre and Performance at The Graduate Center. She is earning a certificate in Interactive Technology and Pedagogy (ITP) and a New Media Lab Student Researcher.

Leave a Reply