By Jesse Rice-Evans

Welcome to the new Visible Pedagogy series on Exploding Access: Trauma, Tech, and Embodiment. In this series, three other CUNY-based writing teachers and graduate students discuss their abundant own views on access, including gender expression and identity, teaching while “crazy,” and integrating self-care in the neoliberal classroom. Authors Chy Sprauve, Zefyr Lisowksi, and Andréa Stella tackle their own experiences and make connections to how they work to reflexively re-center access in their teaching. We can all benefit from their empathic and critical perspectives. Stay tuned!

In this introductory post, I tell my own story of in/access and how my bodymind’s needs have radicalized my views on access in the classroom.

My first semester at the Graduate Center, I get really sick. At the laundromat, my clothes are accidentally soaked in someone else’s florid detergent, and they come back to my house bearing the fatty smear of fabric softener. I attempt to fold them, carefully, wearing a respirator like a construction worker, but the scent clings to my hands, the couch, the bed.

I Google everything: how to rinse out chemical detergent, eliminate dryer sheet smell, poisoned by laundry detergent, “off-gassing” laundry detergent…

One site suggests boiling the clothes. I test this on my stovetop, but this fills my kitchen with steam, still heavily fragranced. I am wearing the respirator while reading on my couch, before bed, all the windows pulled agape in November, fans plugged in and pointing out, out, please get out. I fill the bathtub with hot water, close the shower curtain, pull open the tiny bathroom window, and shut the door, the fan pulsing on its highest setting. My throat is on fire. My brain is clogged like a pipe. I don’t sleep.

The next few days are blurred by exhaustion. Finals are encroaching, but when I try to pull my laptop to me and sit up to work, I get dizzy and nauseated. On the couch, I set up a mountain of pillows with dirty cases, a cat-hair-covered blanket, an extension cord and gallons of water, a heating pad cranked to full power. I lie back, my hands clutching my phone, and compose emails:

December 4, 2017 Subject: Extension? Hi [XXX], Hope your weekend has been relaxing! This time of year is always tough, and I’m dealing with a lot of fatigue and pain over the last few days. Do you mind if I take an extra day or so to finish up my annotated bib? I’ll likely stay home tomorrow as well. In other news, I’m bummed that your course next term conflicts with the only digital anything course in the entire English department catalog! Sounds super interesting and I’m sad to miss out. Thanks!

I never explain that I was poisoned by my laundry.

I pull up a big project from my phone, propping my elbows on pillows stacked nearby. When I tap the “edit” icon, I notice a microphone symbol along the bottom row on the keyboard. Tapping it, I begin to speak, even my voice weakened; word by pained word, my voice appears, alphanumeric, across the screen. My heart pounds and I’m unsure if it’s chemical or the thrill of stumbling onto a tool that changes my work forever. By the time the last traces of stink have drifted out my windows, I have almost 40 pages of notes towards my bibliography.

Even before this acute disabling event, I knew I needed new approaches to my own work as a student, and it seemed obvious to me that the practices I was developing out of necessity as a student would impact my teaching. When my 80-minute commute to City College became untenable, I was approved to teach hybrid composition courses: I enrolled in workshops for Blackboard, spent hours exploring new educational technology tools, and developed a website housing all of my course materials. I did this from my couch, in what my partner calls my nest: pillows, stuffed Pokémon, heating pad, all my devices plugged into a power strip.

Talking the body is always an uphill battle: in academic spaces, the body is placed secondary to the mind (as if they are extricable). Developing illness is difficult to explain to anyone without illness: Susan Sontag writes of these two kingdoms, and I imagine them parallel but inaccessible to each other (except maybe through email).

Without a recognizable diagnosis, it’s even worse.

Eli Clare, disabled activist and brilliant writer, tackles this liminality in Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure: “These experiences of disorientation and devaluing are often called misdiagnosis, as if the ambiguity and ambivalence contained within diagnosis could be resolved by determining its accuracy” (42). This is what institutions demand for recognition: a name for what it is. A signed, notarized, official letter from a healthcare professional to prove that my body hurts all the time the way I say it does. Gatekeepers hold this space hostage; I didn’t become trouble until I became unable to be ignored.

In planning this series for Visible Pedagogy, I want to explicate how access is more than longer exam times, as prescribed by a medical professional on institutional letterhead.

For me, access is working from bed and counting that as work. Access is your grandmother died last week, turn your work in by the end of the semester. Sneak snacks into class, use the bathroom, ask for help, receive help when you ask. Cancelling class when you need to. Conference funding, reservable rental scooters, unscented cleaning products. Long breaks. Normalizing lying down in meetings. Mental health absences. Physical health absences. Attendance not counting towards course grade. A contract for adjuncts that guarantees courses, guarantees pay, guarantees that retaliation will not be tolerated.

Eli Clare wants us to shed the shame of our bodies falling apart, to recognize the implication of chronicity, how, despite the reputation of academic schedules as forgiving, there is always another fellowship deadline, a pressing CFP, daytime conferences and evening panels and never enough time to do it all. How can I reconcile my narrative with the priorities of the academy, having to spend all my time off recovering from my time on?

For us as graduate teaching fellows or non-tenure-track faculty, this means loosening our obsession with bureaucracy. We cannot ethically demand medical paperwork for accommodations in a country where medical insurance is pay-to-play. When students ask for help, try believing them.

As I am working on this piece, my friend Liz Bowen, PhD candidate at Columbia, posts this to her Instagram:

I message her, feeling the familiar burn of anger at the inequity of the academy. We vent, and I ask if I can share her post here. Something about a critical mass demanding legitimacy, belief from a deeply ableist institution feels terrifying. Her story feels so familiar.

This can start small: a revised accessibility statement on the syllabus. Zoë Wool compiles a collection of models HERE. My co-teacher Andréa Stella—from whom you’ll be hearing soon in a Visible Pedagogy post on trauma-informed pedagogy as a teacher with PTSD—and I decided on: “We take seriously the needs of our students. This includes making accommodations for neurodiversity, learning disabilities, mental/emotional health, and other situations not listed here. Please let us know how we can support your learning.”

This is a start but I know we can do better.

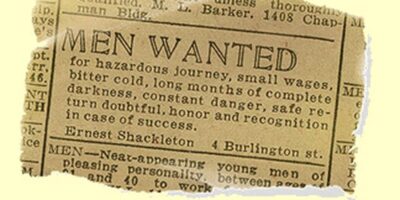

![Meme by @hot.crip that reads: "how to accommodate people with disabilities: NO ask them whats wrong with them" [sticker: "oops try again"] [line break] "ask them how you can make an experiene safer for them" [sticker: yasss]](https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/2881/files/2019/03/IMG_0662-816x1451.png)

Leave a Reply