By Claire Cahen

Two years ago, in the middle of a General Education Seminar at City Tech, I realized that place-based pedagogy had become a best practice for educators. It had long been a necessity in the fields in which I traffic (Urban Studies/ Urban Planning/ Environmental Psychology), but the leaders of the seminar were encouraging departments like Hospitality Management and Biology to consider taking their students out of the classroom and into the streets. They noted the advantage of field-based exploration is to “allow students to become the creators of knowledge rather than the consumers of knowledge created by others.”[1]

I agreed with this statement then and stand by it now. Place-based learning is a key component of my courses and not just because it has to be. I find students learn best through practical engagement with the socio-material world. Place-based learning makes it clear that, in key ways, we are discussing topics that students already know well. They have lots to say, for example, about gentrification. They are living it. When we do site visits together, they can point to it, literally and metaphorically.

But what becomes of place-based pedagogy with distance education? What forms can it take in a pandemic-ridden world where fieldwork isn’t all that safe? In this post, I highlight some creative strategies that educators (especially on the Commons and the OpenLab at City Tech) have used to facilitate place-based learning without relying on “traditional” fieldwork. I also discuss some ethical issues related to place-based learning in a pandemic. Lastly, I recognize what has been lost for those of us who relied on in-person fieldwork in our classes and think about how we can give ourselves some space to grieve.

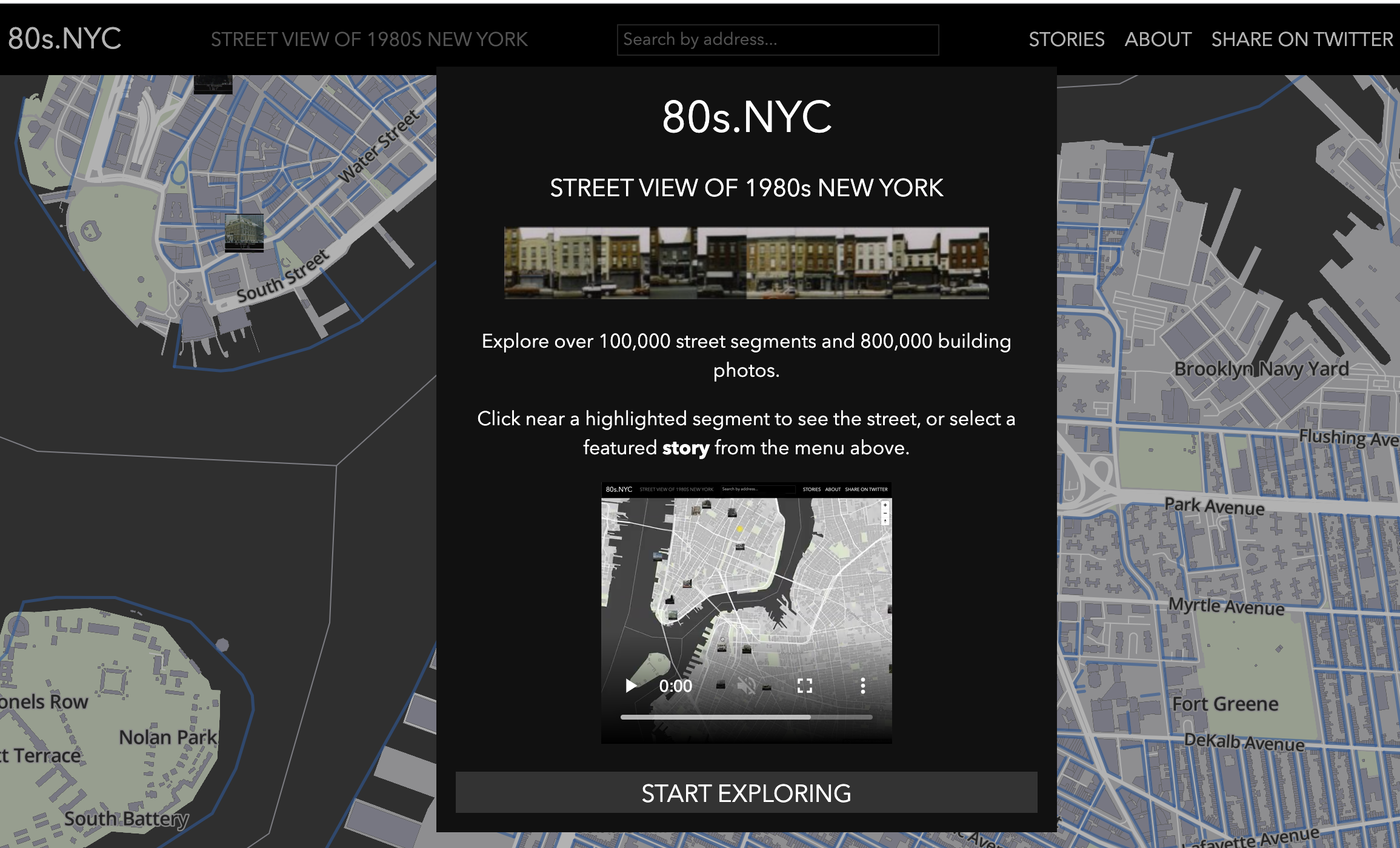

Digital resources are a great way to maintain a focus on place without requiring an in-person visit. A few years ago, in my course Psychologies of People in Place: From Climate Change to Gentrification, a student asked me if they could do their final project–a site analysis–on an internet forum. I answered that a digital space was indeed a space and could be analyzed. Little did I know that all my students would be relying on digital research a few years later. Digital media, more specifically, is a compelling way to spark class discussion. For example, in an OER on Café y Barismo: Culture, Consumption and Anthropology, Jose A. Torres-González suggests that, to think about high-end coffee shops, students break up into groups to watch short documentaries on the topic. Each group then focuses on one concept: production, exchange, consumption or power. In a course on Work, Culture and Politics in New York City, Dr. Rodriguez invites students to make portfolios that include original photographs or film footage of a site. Introduction to Sustainability similarly asks students to use open source photo archives of New York City in the 80s. These are all great alternatives to in-person fieldwork: group discussions and other activities such as buddy systems and think-pair-share provide occasion for connecting over the material. Students who want to supplement this digital and archival work with in-person visits have the option of doing so. Plus, photographs and movie stills provide snippets of people’s lives not as easily captured on a walking tour: training the gaze on images allows students to catch details they might have overlooked in person.

Homepage of 80s.nyc, created by Brandon Liu and Jeremy Lechtzin.

Other instructors opt to explore place through memory, having students share on course sites stories of places to which they are attached. In Learning Places: Understanding the City, Professor Muchowski and Professor Duddy’s first blogging assignment has students write about a public building or space in their neighborhood. Students describe watching these spaces evolve over their lifetimes and reflect on their experiences. The professors connect with students over the meaning of place by sharing their own ties to the sites students mention. For example, Professor Duddy exclaims in (a blog) response: “I used to live at 98th and West End…there was a great playground at 95th where we would take our daughter.” Early in the pandemic, I remember reading these posts and the professor-student exchanges. They were a welcome reminder that, as isolated as our lives were, places and memories could give the classroom a shared foundation. These kinds of prompts also provide an entry into the concept of social memory, reflecting how collective narratives of places and events both rewrite the past and construct the present.

Another way to explore place-based learning is to orient the class around a space that has gained increased relevance in the pandemic: the home. The Teaching and Learning Center’s own Fernanda Blanco-Vidal focuses her course on the meaning of a home and how this has changed through periods of shelter-in-place and tentative re-openings. In most of my courses, I also include feminist theorizations of home. As a first assignment, I ask students to interview someone close to them to try to understand their placemaking practices. How has this person come to make a life (or not) in the spaces they inhabit? I had one student who became very enamored of Clare Cooper Marcus’ classic text on The House as Symbol of the Self [2]. They spent the semester exploring how their family’s sense of being was entangled with the building where they lived. Another student chose to draw a visual essay on their building, exploring the experience of feeling at times deeply alienated from their home. These are intimate topics, but, in this case, students appreciated being given the space to think through issues that cut to the heart of daily life.

Empty playground in Brooklyn, early spring. Photo by Brett Kunsch on Unsplash.

That said, there are ethical concerns with focusing on the meaning of home, particularly during a pandemic which has magnified issues of housing insecurity across class and race lines. A survey of CUNY students before the pandemic showed that 55% had been housing insecure in the previous year and 15% had been without homes [3]. Pre-existing housing inequities are part of what made the call to shelter-in-place so thorny [4]. A house is not necessarily a home. Sometimes it isn’t even shelter. Housing remains a core theme in my courses, but I would never require that students write about their own housing situation. Instead, I offer a range of social texts on issues from gentrification to the fight to save public housing to homelessness to housing precarity in the pandemic. Students who want to write about their own relationship to the domestic sphere or the idea of homemaking are welcome to do so, but that path is theirs to choose, and not mine to mandate.

Similarly, I draw again here on Fernanda’s intuitive pedagogical style to note that, for those of us who teach issues like climate catastrophe, talking about a traumatic future during a protracted crisis may not be the most ethical approach. Fernanda asked students point-blank whether they wanted to talk about climate catastrophe when the pandemic hit, and, in fact, the consensus was that they were interested, but also wanted to understand what provoked the current debacle. Had students said, no, climate catastrophe was too much, she would have dropped it that semester.

Lately, I have been making a lot of syllabi for job applications. No matter the topic, I tend to include modules on pandemic challenges to the “just city” and find myself mourning how much the stakes of fields like Urban Studies have shifted. Speaking at least for myself, I have moments of overwhelm when I consider that cities are changing rapidly without my having been able to be a witness to it. I have spent the better part of the past two years sheltering-in-place and most of my knowledge of what is happening “on the ground” comes from the news and the occasional academic publication. I’ve tried to accept uncertainty. I have also steadily been disabused of the illusion of a safe return to the places I loved. I haven’t entirely given up on prediction, but feel foolish asking students to imagine what the city will look like when this all “ends.” Moreover, site visits and walking tours were the parts of the semester I most looked forward to. I loved watching course theory come to life for my students–and for myself. In addition to large traumas, Covid has brought countless non life-threatening but nonetheless real deprivations. I have had to recognize that much like the loss of classroom community, the loss of place-based learning and fieldwork is something I need to grieve.

I hope this post has highlighted some alternatives to in-person fieldwork. Some of the strategies discussed here have advantages, and one of the wonderful things about leveraging technology and digital pedagogy is that it is so much more flexible. It makes students’ lives easier. But this pandemic hasn’t been easy for fields that are dependent on place-based teaching and learning. I am OK with mourning that.

Claire Cahen is a PhD candidate in the Environmental Psychology program at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY). She is a Teaching and Learning Center Fellow and has taught courses such as Psychologies of People in Place, and Research Methods for Environmental Studies.

References

[1] Smith, Gregory A. (2002) “Place-Based Education: Learning to Be Where We Are.” The Phi Delta Kappan 83.8. 584-94. JSTOR. Web. 13 June 2014.

[2] Cooper, Clare Marcus. (1974) “The House as Symbol of the Self,” in Lang, J. ed., Designing for Human Behavior: Architecture and the Behavioral Sciences, Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross, Stroudsburg, 130-146.

[3] Goldrick-Rab, Sara, Coca, Vanessa, Baker-Smith, Christine and Looker, Elizabeth. (2019) City University of New York #Real College Survey. Accessible at: https://hope4college.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2019_CUNYReport.pdf

[4] Pierre Gilbert & translated by Oliver Waine, “Covid-19, War, and Working-Class Neighborhoods”, Metropolitics, 5 June 2020. https://metropolitics.org/Covid-19-War-and-Working-Class-Neighborhoods.html

Leave a Reply