By Sarah Hildebrand

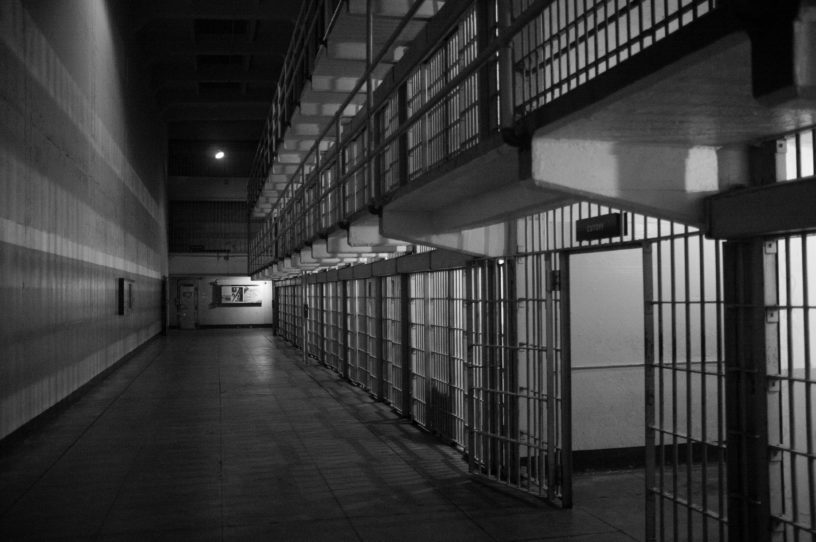

As a rape survivor, my role as an instructor in prison was difficult. I had to manage comments from Correctional Officers (COs) who referred to my students as “a bunch of rapists and murderers” and one who habitually told me to “stay safe in there.” Another told me he always did extra rounds when there’s “a female” on the unit. I know at least the last two officers meant their comments as acts of care, but the undertones of gender-based violence were triggering nonetheless.

As witnesses to the violence of mass incarceration, all prison educators experience vicarious trauma. Comments from COs aside, I taught students who had not only experienced trauma in the past, but were actively experiencing it collectively every day I saw them in class.

I was also exposed to my students’ individual traumas when they connected readings to their personal lives both in group discussions and in writing. In my composition course, the first formal essay was a personal narrative, and although the assignment was open-ended, many students chose to write about the events that landed them in prison. I read stories of child abuse, racial profiling, and loss—multiple stories in which people shot someone or got shot at.

When reading these narratives, I found myself writing questions in the margins that I didn’t really want answers to. Next to a scene involving gun violence, I scribbled: “The story becomes a bit rushed here. Could you slow this scene down?” After reading others that vividly described traumatic events in the foster care system and time spent in Iraq, it felt unsettling to write “Great work!” or “Nice job!” at the end to celebrate well-written work. I found myself leaving longer comments, trying to attend to both the writing technique and emotional contours of the essays.

For me, the vicarious trauma of witnessing was compounded by isolation. For most of the semester, I was the only faculty member on campus the day of my class. It was easy to feel like I had no outlets for processing shared experiences or collaboratively troubleshooting classroom issues particular to prison environments. While I could’ve hunted down email addresses for other educators in the program, honestly, the idea of reaching out felt shameful. I worried that initiating any sort of contact might be interpreted as an inability to handle this kind of work. This concern felt particularly palpable to me as a contingent faculty member.

Although I’d spent time in prisons before doing research—and know people who are or have been incarcerated—I still felt underprepared for some of the particular challenges of teaching college in prison. Working in carceral spaces will always entail the risk of vicarious (or even direct) trauma, and, because of this, actions need to be taken to better support faculty and reduce harm.

One way to resolve some of these issues would be to institute structures to help normalize communication and collaboration. Mentorship programs—even informal ones—could go a long way towards stress reduction. New faculty could be paired with returning faculty, meeting once before the semester begins to establish rapport and answer questions, and then subsequently checking-in via email. Doing this even just once or twice throughout the semester would provide both parties with the opportunity to process the experience and create a sense of solidarity—without placing the burden on new faculty.

I’ve also spoken with educators in other prisons and jails who have team-taught their courses. While team-teaching can entail more prep. work to coordinate lessons, it also provides more emotional support when dealing with the myriad dynamics of prison classrooms and troubleshooting logistical issues encountered when teaching with limited resources. Team-teaching also has the added benefit of allowing students more opportunities for individualized instruction.

Regardless of how many educators are in the room, it would be helpful to have more useful (and paid!) professional development workshops and orientations to train them. While there’s no way around the rules, security, and invasions of privacy that occur daily in the prison system, more thorough orientations could help educators be better prepared for these realities. My first day on the job I felt lost and confused. I had never gone through the exact process of entering the campus or going through security. I had to repeatedly ask COs for directions since I had never seen my classroom before.

The routine of the prison was so well-established that I was expected to fit in seamlessly. I was nervous about doing something wrong and distressed that I seemed to be slowing things down. It was weird passing through a metal detector on my way to class and having all my belongings thoroughly searched—from the pockets of my jacket to the insides of my shoes. Because all course materials must be preapproved before entering the prison, any last-minute handout or assigned reading was technically contraband. As the semester progressed, I got braver and managed to smuggle some through with the rest of my course packet, but it was always a bit unnerving.

In order to be approved as a volunteer within the prison by the Department of Corrections, you must complete a training that consists of watching a series of outdated videos on how to assess suicide-risk, abide by the Prison Rape Elimination Act, and avoid being manipulated by incarcerated individuals who are framed as seeking to actively involve you in illicit activities. While the first two videos were poorly made but necessary, the third was largely just stigmatizing, perpetuating stereotypes that imagine incarcerated individuals as dishonest and dangerous.

Instead (or in addition), it would be helpful for universities that have prison education programs to provide their own training on the skills necessary to be effective educators in prison environments—instruction on how to adapt the outside educational experience on the inside, and trauma-informed pedagogies that can respond to the educational and emotional needs of incarcerated students. There should also be workshops devoted to educator-wellness that emphasize the bidirectionality of trauma, the risk involved with prison education, and the resources available to navigate it.

While some programs might lack the infrastructure to adopt these practices, and no practice will fully resolve the issue of vicarious trauma, we could be doing more to lessen its impact. Teaching in prisons is an incredibly rewarding experience, but it comes at a significant cost. People often ask why I chose to teach in prisons at all. I tell them I believe in social justice—that prisons should be abolished and that everyone should have access to higher education. I tell them I want to play a more active role in achieving these goals. After participating in this program, I still hold these beliefs and think more people should be part of this project. But I also think we should be honest about what this type of pedagogical activism entails for instructors and ensure that they have adequate training and support.

Rebecca

Finding this article is such a relief. For the last three months I’ve been teaching in a carceral environment and have also struggled to discuss the emotional toll of the work with my coworkers. Everything you describe is so relatable. I wish there was a support group for this kind of thing. Thanks for putting words to what I’ve been feeling and for the social justice work you do!